Psychology as a field was planted by the broken philosophy of the 19th century, and now it grows through a broken system of grants and tenure. As such, it perpetuates myths that psychologists neither see nor care to see. Here are six of them:

1. Impulsiveness needs an outlet

This myth permeates one of the greatest genres to grace the silver screen—buddy cop movies. If the uptight member of the duo doesn’t learn to loosen up and be more impulsive like the fun one, then he’s headed for an early grave of suppressed stress. Yet impulsiveness, or acting without thinking, doesn’t relieve stress, it increases stress.

Like obsessive thoughts or compulsive behaviors, impulsiveness is an avoidant behavior in that it’s a distraction from the pain of latent anxiety. Avoidance only makes the anxiety worse because when we avoid anxiety it confirms in our mind the possible threat of the anxiety. The suppressed archetype and the impulsive archetype are two sides of the same coin—both represent an immature way of managing anxiety.

2. A single, traumatic event in childhood causes neuroses in adulthood

It’s possible that a traumatic event can shape our lives, but it’s rarely one event. And if we can pinpoint one event, it’s not the event but how our family and friends reacted to the supposed cataclysm. Let’s say our twin brother died when we were in grade school. If we’re still subconsciously, negatively influenced by this years later, it’s not because of Billy’s death but how our mother became grief-stricken and unemotional. Trauma is often diffused over many years. It comes from a long series or either abandonment or indulgences—either too little attention or too much—as a result of the alleged trauma. Single, inciting incidents make for a great story to tell ourselves, but they are seldom more than a scapegoat for insecure attachments.

3. Uncovering the cause of a neurosis cures the neurosis

It makes for a Hitchcockian plot when a man delves deep in his subconscious to figure out the root of his behavior, understands the cause, and in an instant is able to move on with a new sense of psychological freedom. Except real life doesn’t make for an economical hero’s journey. If we have an anxiety disorder, there’s rarely one cause but even if there is only one cause, uncovering what it is does little to lessen the anxiety. We may see the tin can from which the worms have crawled, but this doesn’t clean up the worms. Until we do the work no one wants to do by confronting our perceived threats—which usually involve parental relationships—no single “aha” moment will make much of a difference.

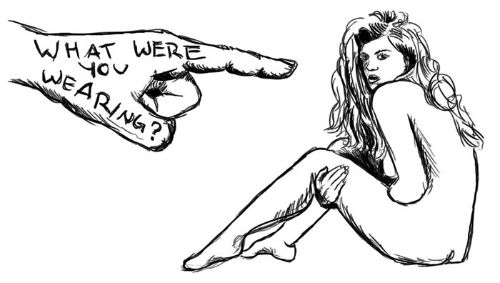

4. Victim blaming blames the victim

I’m probably preaching to the choir here, but it’s worth repeating: “Victim blaming” is a phrase that inhibits more clear thought than a political rally. No one has ever blamed the victim—not in the West and not in the past three centuries. “Victim blaming” merely lets a victim know his part in perpetuating his circumstances. It’s called being a responsible adult by uncovering increasingly expansive layers of awareness, which has nothing to do with blaming anyone.

5. We can replace bad habits with good habits

An idea—or hope, rather—that became popular during the mid 20th Century, with the rise of cognitive psychology, is we can merely exchange a bad habit by partaking in a good habit instead. It’s the rationale behind replacing negative thoughts with positive thoughts, or chewing gum instead of smoking. This only works if the good habit diminishes the psychological issue that causes the bad habit. Attending a 12-step meeting instead of drinking could take the rage out of our alcoholism if the relationships formed in the meeting relieve the anxiety that caused the drinking. But the bad habit cannot simply be covered up or retrained. Whatever is causing the bad habit must first be managed on its own, which creates a space for a good habit to fill, potentially.

6. Reason and emotion are inherently at odds

These are two different modes of processing information and evaluating the world, but this doesn’t mean they’re inherently at odds. They can be at odds, and they are in most people, but this doesn’t mean it’s necessarily so. Our emotions are approximate insights based on our many beliefs and perceptions about us and the world. These beliefs and perceptions that undergird the emotion may be correct, but when they’re incorrect, then they will contradict reason.

We may know rationally it’s good to leave our girlfriend because she became fat, but we may not feel like it’s the right thing emotionally because back of our emotion is the belief that we don’t deserve to have a girlfriend who takes care of herself. When we have a conflict between our reason and emotions, let’s not take that as a sign we’re inherently flawed as men but rather that we’re flawed as a man. Instead of stewing in our supposed helplessness, let’s take on the responsibility of understanding the source of our inner conflicts.

Conclusion

The myths presented here represent only a few of the issues with psychology. To fix the field, we need to correct them all. But to fix our psychology, correcting even one of these errors sets us up for a life of ease and success.

Read More: Are You On A Treadmill Of Materialism That Goes Nowhere?

Leave a Reply