Pressure reveals the man. Take a man, any man, and subject him to extreme stress. Subject him to sleep deprivation or fear, exhaustion, and the uncertainties of climate and personal safety, and you will see the soul of the man. This is what I always liked about extreme stress. It reveals the true essence. A young military trainee thrown into an extreme environment or hostile fire zone, or a young lawyer taking on his first big high-stakes jury trial, will both reveal their inner natures by their performance and responses to pressure.

A man’s response can’t be faked. It just can’t. Some men like to talk big, to pound their chests about one thing or another. But those who have truly seen the face of the Beast know it is not a joke, not something to be taken lightly. Because the Beast is avaricious, and he feeds on souls.

And sometimes we find out things about ourselves that we would rather not know. But it is a fascinating exposition. It is a wonder to behold. Those who enter these dark arenas are driven by a passionate desire to test their cold steel against the flesh of the world. It is truly the greatest drama of all.

And you never can tell. You never can. That man you see over there, for instance, who seems to be a quiet, bespectacled introvert, may turn out to have the soul of a lion. Or that peacocking, muscled braggart over there may be revealed to be a man of straw at the moment of truth. Or vice-versa. You just never can be certain.

But every man has a breaking point. Every man. I remember reading a story in Tom Mangold and John Penycate’s book The Tunnels of Cu Chi some years ago that resonated with me and stuck in my memory. I want to relate it here.

Jack Flowers was a college dropout who got drafted into the US Army the late 1960s and found himself serving in Vietnam. Because of his educational background, he was put through an officer training program and was assigned to an engineer battalion. Over time, he began to feel the stirrings of an unsuspected militancy, and became more and more interested in taking an active part in the fighting. Two experiences helped push him in this direction. One was getting called a REMF (rear echelon motherfucker), and another was seeing a dead comrade getting pulled out of a Viet Cong tunnel.

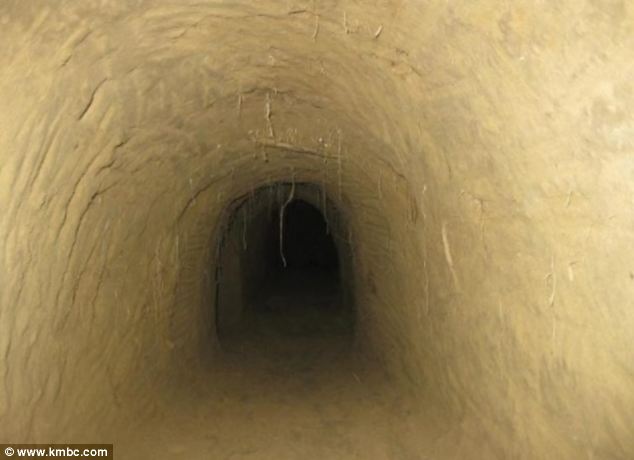

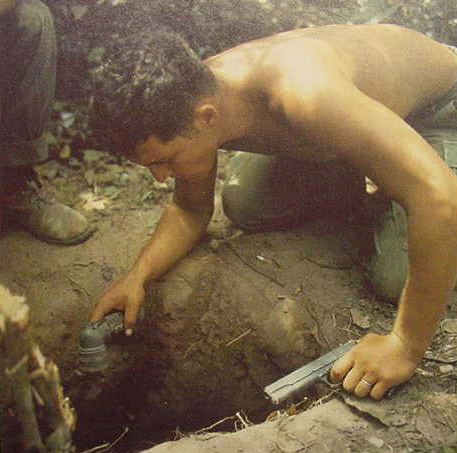

Like some men, he was driven by a secret pride that felt compelled to test the limits of its endurance. Flowers would soon get his chance. Against the advice of his friends and family he decided to join an elite group of “tunnel rats”, which specialized in locating and destroying the enemy in its dark honeycomb of underground lairs. Armed only with a switchblade, flashlight, revolver, and a grenade, a tunnel rat had to go down into the tunnels, seek out the enemy, and kill him in one-on-one combat.

And by all accounts, combat in the claustrophobic tunnels was a horrifying experience, profound beyond words. It was as personal as the war ever got. And there was no way to fake it.

The man who had trained and led the tunnel rats which Flowers joined was a smoldering, inscrutable soldier named Sergeant Robert Batten. He was nicknamed Batman. And he was both widely feared and respected for his extraordinary body counts and ruthless leadership abilities. Batten was a legend, and he knew it. He was a tough, cunning, and deeply aggressive man; someone who might have been a nonentity in regular life but had come into his own during the war.

The Viet Cong knew who he was, and had put him on their “ten most wanted” list. Captured VC spoke of him with awe. Batten didn’t like most officers, and he didn’t like poseurs. Incompetents and fake heroics could get men killed. Everyone had to pull his weight; there was no rank in the tunnels. “We’ll get along just fine if you stay out of my way” was his curt statement to Flowers.

The tunnel rats were a highly professional unit. There were many Puerto Ricans and Mexicans, men coming from cultures for whom the martial spirit of Old Spain had never really died, men who were not squeamish about using a knife, men who had never gotten much from life and expected little from it. There were also many quiet, unassuming hillbilly types, men who were otherwise soft-spoken but who became unglued in the tunnels, relishing in the brutality of man-on-man combat.

Man is a complex and many-layered being.

Slowly and steadily, Flowers built up his credibility with Batten and the tunnel rats and earned their respect. He knew he could never ask one of his men to do something he himself would not do, so he personally went on many tunnel missions. He began to lead his unit in fact as well as in theory. He was even wounded by a grenade on a tunnel mission with Batten. And his confidence soared. He was a good “Six” (tunnel rats used the term “Six” as the code word for leader). He had wanted to prove to Batten that he was his equal, that he was a good fighter, and a good leader.

But Batman was unimpressed. He sized up Flowers in his own ruthless way, and issued his own verdict. One day, Batten said to him, “You’re not a killer, Six, and that’s your problem. You’re pretty good, the best Six I ever had, but you’ll fuck up somewhere. Charlie hasn’t killed a rat for quite a time. And you’ll either let him get you, or you’ll get yourself.” Flowers was stung by the remark but let it go. Batten rotated out of Vietnam soon after, after having served three back-to-back tours.

One day, Flowers and his men were out on a mission. A tunnel complex was discovered and someone spotted a VC disappear down a shaft that went straight down twenty feet before angling off horizontally. They thought they had the VC cornered. He had to be down there, they thought, crouching in the horizontal tunnel with his AK-47 at the ready.

Flowers was exhausted but pressed on. He looked down the shaft. It was a rat hole leading straight to hell. He decided to have his men lower him in a seated rope cradle (called a Swiss seat) halfway down the shaft. They would then drop him, and he would hit the bottom of the shaft so he could take the cornered VC by surprise.

One of the rules of the tunnel rats was never to fire more than three shots from a .38 revolver, as this would reveal that the shooter needed to reload. As Flowers was lowered slowly down into the shaft, his men looked on in grim and fearful silence. He was soaked in sweat, throbbing with adrenaline, and he kept hearing Batten’s voice.

You’ll fuck up somewhere, Six…you’ll either let him get you, or you’ll get yourself.

His plan was to hit the ground and immediately get off a head shot against the VC before he himself was hit. He fully expected to get hit, and, as he was lowered slowly into the hole, he tried to visualize the best shooting position to get into. Finally Flowers gave the signal and he was dropped into the inky blackness. He hit the ground and started firing. And kept firing. After his men heard six shots ring out, one of them threw down a second revolver.

And then there was silence. When the acrid tang of cordite cleared, Flowers breathlessly tried to make out what was in front of him. There was nothing but a blank dirt wall. No VC with a gun. Just a cluster of bullet holes in the damp earth. Exhausted and stressed beyond limit, he had fired all six rounds against an imaginary target. And the rules said no more than three shots. Flowers rubbed his fingetips against the six neat holes in the packed earthen wall, and then put his head in his hands. And in his mind, he heard Batten’s voice.

You’ll get yourself, Six. You’ll get yourself…

Word of the incident found its way back to Flowers’s commanding officer, and he was relieved. Not much was said, but it was clear that his men had lost confidence in him. For the good of the unit, he was shipped out of the area to another part of Vietnam. There were no goodbyes, no pats on the back, nothing. He was just gone. And then Flowers secluded himself and stayed drunk for a week. He had found his limits, and his war was over.

He had done his job with honor, and tested the hazy boundaries of his own endurance and tenacity. He had nothing to be ashamed of. But the merciless struggle leaves no one unscathed. No one is exempt. And as character determines fate, so there is no escape from the pitiless rendezvous between man and his destiny. It makes us and it breaks us with equally callous apathy.

The obscenities of conflict strip us down, flay the protective skins from our bodies, and expose the souls of the innocent to the bitter mockery of the damned.

Read More: The Parable of Aepyornis Island

Leave a Reply