Man cannot live by bread and woman alone. He also needs a myth to sustain him, to console him in his bereavements, to provide a code to anchor his life, and to impart a sense of meaning to this brief mortal existence. Snatch away his mythos, rob him of his ideal, and you banish his spirit to a rudderless drifting in life’s expansive ocean. It is a cruel fate, and one that is far too common.

But for some men, the myth is strong. And it is the last thing to die.

Take, for example, the case of Sir Thomas Malory. He was a English knight who fought in the Hundred Years War, and in 1445 even briefly served in Parliament. He was living at a time in which the medieval notion of chivalry—the age of the knight—was on the wane. Malory had built up his identity around the idea of knighthood, chivalry, and the centuries-old moral code that went along with it. He was bound up with this mythos, and it animated his soul. But returning home to England after his campaigns in France, he found peacetime society unbearable. Here was nothing in his previous experience that he could call his own. And he found his martial skills of no value in the humdrum drudgery of the English society from which he was alientated.

He couldn’t bear it. He writhed and rolled in his peacetime agonies. His way of life was doomed, and he knew it.

At this point, he made a startling reversal. Turning his back on is previous life, he plunged into crime. He broke into the home of a man named Hugh Smyth and raped his wife; he extorted a sum of money from another couple; he raped Smyth’s wife a second time. He committed a long series of thefts, robberies and burglaries, even from a Cistercian Abbey. His crime spree came to an end when he was caught and thrown into prison.

While languishing in the fetid darkness of confinement, Malory managed to write one of the most elegant and transcendent works of early English prose: The Noble Histories of King Arthur and of Certain of His Knights. Time has shortened the name of his book to Le Morte d’Arthur.

Malory implores his countrymen and fellow knights to return to the ideals of King Arthur and his 150 “Knights of the Round Table;” here are found the tragic and timeless stories of Tristram, Lancelot, Guinevere, and many others. He requires of a knight

never to do outrage nor murder…by no means to be cruel, but to give mercy unto him that asketh mercy…and always to do…gentlewomen succor, upon pain of death.

Considering the source, the irony is so thick that one could hardly cut it with Excalibur. In Le Morte d’Arthur, no one ever gets his boots muddy, the skies are always brilliant and clear in Arthur’s ethereal realm, and love and war are wondrously pedestalized. It is about as mythic and idealistic as a writer ever managed.

Because it had to be. Because Malory knew that he, and his myth, were doomed. How can we reconcile the sublime, airy beauty of Malory’s book, with its noble language and moral code, with the base reality of his crimes? How could such a man write such a book?

Because man is a complicated being. That’s why. Complicated, with many faces. He can possess the heart of a monster, and the tenderness of a saint, in equal measure. And somehow, each of these voices needs to speak. Don’t take away my cherished myths, O World! Don’t deprive me of my consolation.

But he knew his time was running out, and he died in prison in 1471. The colophon of his book is a poignant cri de coeur:

I pray you all gentlemen and gentlewomen that readeth this book of Arthur and his knights, from the beginning to the ending, pray for me while I am alive, that God send me good deliverance and when I am dead, I pray you all pray for my soul. For this book was ended the ninth year of the reign of King Edward the Fourth by Sir Thomas Maleore, knight, as Jesu help him for his great might, as he is the servant of Jesu both day and night.

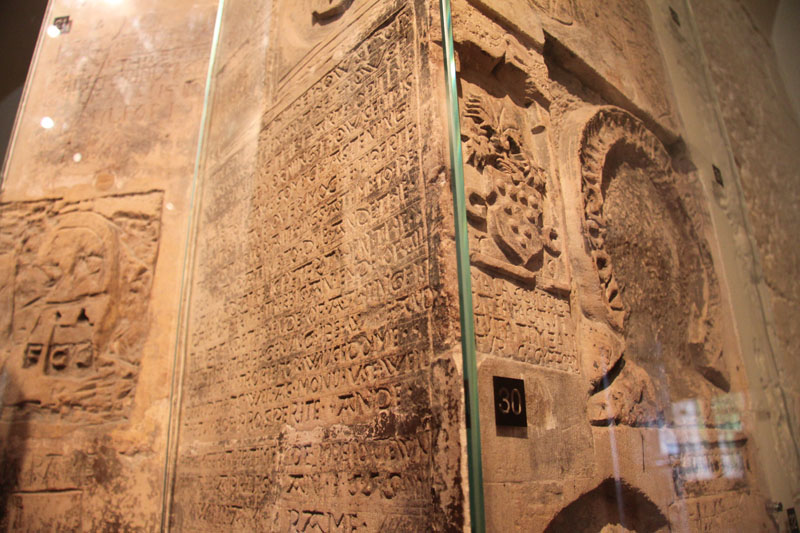

Several years ago I visited the Tower of London. There is a part of the fortress where visitors can look at the wretched cells where prisoners were housed. I remember seeing an attendant on duty there, a pale, grey-haired man sitting at a desk, fidgeting obsessively with a gold cigarette lighter. The other tourists had left the room, and he was looking out the window. I decided to give him something to do, and began to make idle conversation.

“Some of the carvings on the cell walls” I said, “are amazing. It’s hard to believe they were allowed to make graffiti like that.”

He eyed me furtively, taking in my American accent.

“Well, now,” he began, clearing his throat and shifting himself slightly in his chair, “you have to remember that these inmates were rich people, noblemen and such. They had their knives, tools, and the like. They had their ways. Wasn’t much security in those days, you know.” Accustomed to tourist ignorance, he had the impatient demeanor of a man who had answered the same questions a thousand times.

“Yes.” I nodded in agreement, anticipating a yarn.

“Here, let me show you something.” He stood up and walked over to one of the cells and pointed to an amazingly detailed carving in the wall, made by a prisoner centuries before. It was carefully covered with a clear plastic shield to protect it from the curious fingers of tourists. It looked like a coat of arms, or some family or clan monogram. Other cells had similar little carvings, some of very high quality, and all covered with clear little plastic squares. They were all obviously of great significance to their makers.

I tried to imagine the effort the condemned man must have exerted to produce this little piece of gallows artwork. I tried to imagine the sustained willpower that would have been needed. To carry it off would have required the soul of a true believer. It may have been the last thing he ever did. His family coat of arms, his lineage, his house, his earthly identity: scratched out in stone for eternity. There it was. His last and final act. It was moving in its own silent way.

“I can imagine the effort it must have taken,” I said blankly, not knowing what else to say.

“Of course. But it was his identity. That meant something in those days. Much more so than now. We all need something to keep us going, you know.” Then he shrugged his sunken shoulders and walked away.

And I thought to myself, the myth truly is the last thing to die. When that goes, so goes the man.

Read More: Shortness Of Life

Leave a Reply