“If the world hates you, remember that it hated me first.”

John 15:18

Over the past few years, Williston, North Dakota has become famous for its oil boom and the wellspring of opportunity it’s created for men. Advances in hydrofracking technology have enabled oil companies to develop the Bakken oil patch in the western part of the state, attracting men from around the country and world looking for work. While the environmental impact of hydrofracking is well-known, few if any journalists have bothered to look at the trials of the men who go to Williston to begin anew.

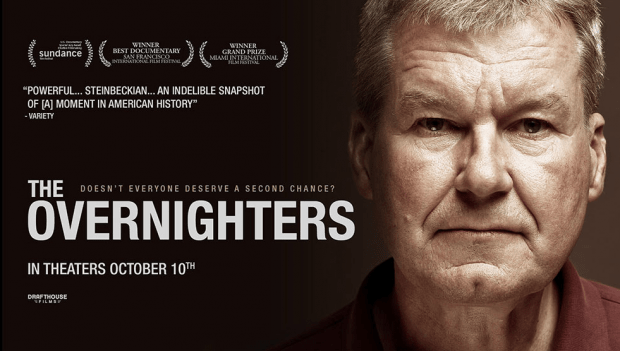

The Overnighters is the first film—or work of art in general—to capture the human element of the fracking boom. The documentary focuses on the Concordia Lutheran Church in Williston, where Pastor Jay Reinke allowed homeless job-seekers (the titular “overnighters”) to sleep while they looked for work. Given the housing shortage in the Bakken, Reinke’s program helped countless men survive the harshness of North Dakota, but it was unpopular with not only his parishioners, but the city at large.

Without spoiling things, the story ends with Reinke’s life—and the lives of everyone he knows—torn apart.

I saw The Overnighters last week at the Maysles Cinema in Harlem, and it was one of the most emotionally wracking films I’ve ever watched. I have a personal connection to the movie: I stayed at the Concordia Lutheran Church two years ago when I was looking for work in North Dakota and knew Jay Reinke well. I ran into director Jesse Moss a few times while he was filming, though I don’t appear in the movie; I also spoke to Moss during a Q&A session at the theater.

The Overnighters is a must-see for the simple reason that it shines a spotlight on the most ignored and despised group in modern America: men. Moss probes the suffering and desperation of working-class men who leave their families behind looking to make something of themselves. His film is a unique portrait of the dire straits that these men find themselves in and the lengths they’ll go to to survive.

Fear Of A Male Planet

The time I spent in Williston—and at Reinke’s church specifically—was one of the most surreal experiences of my life. Every night at nine, Reinke opened up the doors and the church transformed into something resembling an army barracks. Men set up their cots, cooked, played chess, chatted and more before the lights were turned out at eleven. At 6:30 am on the dot, Reinke would wake us up by singing hymns—“The Lord God is my strength and my song, and He has become my salvation!”—as we rushed to clean up the church and get to work.

The tensions surrounding—and within—the Overnighter program were palpable. I once had to help defuse a fight between two overnighters, and Reinke took a lot of heat from the Williston Herald for “harboring” sex offenders, as he believed that everyone deserved a second chance. While I was staying there, the church elders also pressured Reinke to limit the Overnighter program to just 30 men. However, there was a real camaraderie between Reinke and the overnighters, as we shared job tips, went to bible studies and devotions, and tried to give each other a helping hand.

So many men were aided by Reinke’s sacrifices—even if they didn’t succeed in finding permanent work—that it was astounding. One guy I befriended had come from South Carolina with literally nothing but the clothes on his back, after struggling with meth addiction and homelessness for years. A month of doing temp work in Williston and he had earned enough to buy a computer, cell phone and car. The Concordia Lutheran Church was an oasis of stability for us in the chaos of the oil patch.

The Overnighters captures the atmosphere of the church perfectly. The film follows a number of overnighters (none of whom I knew personally) looking for work, most notably Keith Graves, a truck driver from L.A. and sex offender. Reinke’s decision to move Graves into his own home—and Graves’ subsequent betrayal of his trust—is just one of the movie’s many heartbreaking moments. As one of the film’s subjects exclaims, “I came out here to save my family, and it’s probably gonna cost me my family.”

The Martyrdom Of Jay Reinke

In its depiction of Jay Reinke, The Overnighters also paints a portrait of what it’s like to stick to your principles when the whole world is against you.

During my Williston stay, I found Reinke to be difficult to get along with at times. He was egocentric in many ways, had a short temper and was prone to outbursts: for example, he once got into a vicious argument with an overnighter wearing an Obama T-shirt. However, his act of compassion in sheltering us—becoming a pariah and straining his relationship with his wife and children—was something no one else in Williston did, either while I was there or after the overnighter program ended.

More importantly, Reinke never tried to pretend that he was better than us. When I first showed up at the church, he was honest, telling me, “When you came in the door, Matt, I thought the same thing I always do when we get a new overnighter: ‘God, not another one.’” It was obvious he was struggling against his own instincts in running the program. It would have been much less painful for Reinke to abandon the overnighters, to take the easy way out, but he never did.

And as Moss reveals in The Overnighters, Reinke’s own motivations for running the program were far more complex then anyone could have imagined. Without spoiling things, he reveals a dark secret in the film that was so shocking it made me shout “Oh my God!” out loud. As I said to Moss after the movie, both of us suspected that Reinke was hiding a great burden, but nobody could have guessed that this would be it.

The Death Of The American Dream

The Overnighters also succeeds in other, subtler ways. Moss had a level of access to his subjects that is rare in documentaries: for example, Reinke’s dark secret is revealed in what was supposed to be a private conversation with his wife. Another segment of the film shows a fat lady chasing Reinke and Moss off her property at gunpoint. At points during The Overnighters, it almost seemed like Moss’s subjects didn’t even know he was there.

It’s because of all this that The Overnighters is one of the best movies I’ve seen in years. Even if I didn’t have a personal connection to its protagonist, I would have still been moved by the film. It’s an affecting depiction of male suffering, redemption, and sacrifice, one that doesn’t resort to Manichean morality or hokey cliches. The Overnighters investigates the men and women whose lives are affected by the fracking debate and usually ignored by the media.

The message of The Overnighters, if there is one, comes in a short scene midway through the film. Reinke is listening patiently to a job-seeker discuss his meth addiction, his sexual past, and how he was conceived as a result of his mother’s rape. As the man breaks down into tears, Reinke hugs him and tells him, “You and I are more alike than we’re different. We both have darkness within us.”

Ain’t that the truth.

Read More: “Rick & Morty” Shows The Utter Hopelessness Of Modern America

Leave a Reply