Last week, Roosh V published a short piece introducing the new term “neomasculinity.” The article described how the term “red pill” had its limitations. It had become shopworn, and vague from overuse. He explained why a new, more precise word was needed to describe our guiding ethic. The article provided a list of the salient features of what we call neomasculinity.

We will now build on that foundation, and describe some of the origins of neomasculinity in the popular culture from the 1980s to the present. It is a task that is long overdue. Previous attempts by the mainstream press to describe the manosphere have been so intellectually dishonest, so polemical, and so shot-through with errors, that anyone sincerely writing on the topic can hardly fail to do better.

Origins in the 1980s and before

The 1980s in America were generally an optimistic decade. The country was beginning to recover from the effects of the lost war in Vietnam, Watergate, inflation, and the Carter presidency, and the deep cynicism that came in the wake of those unsettling historical events.

The seventies had reveled in nihilism and apathy, and the popular culture reflected this; films like 3 Days of the Condor, Apocalypse Now, Taxi Driver, and Vanishing Point are examples of this pervasive feeling. But the dawn of the Reagan era seemed to promise a new beginning, however illusory this proved ultimately to be.

Reagan-era political rhetoric seemed to reflect a new feeling of breezy optimism, of can-do pragmatism, and a comforting faith in traditional institutions. Films like Back to the Future, the many fantasy-laden epics of Steven Spielberg, and the thriving music culture of the 1980s, all seemed to indicate that the ghosts of the 1960s and 1970s had been banished for good. We were great again, because Sylvester Stallone and Bruce Springsteen said we were. And who could argue with Rambo or The Boss?

Enter generation X and the millennials

And yet the promises of the 1980s seemed to evaporate faster than Reagan’s popularity after the Iran-Contra affair. The 1990s ushered in a new era of cynicism, apathy, and bitter alienation. Nothing could be more telling, in the popular culture, than the replacement of the glitzy hair-metal bands of the 1980s with the despairing agonies of bands like Nirvana and Alice In Chains. A changing of the guard had come, and with a vengeance.

Alan Bloom’s seminal The Closing of the American Mind (1987) seemed to set the tone for the new decade. Its thesis was that cultural relativism and radical liberalism had effectively destroyed American education (and looking back on Bloom’s book now, it is clear that he was absolutely correct). Gen Xers were also pervaded with the feeling that there were few things in their world worth fighting about: the great struggles of the past (foreign wars, civil rights, etc.) all seemed to have been won.

Author Francis Fukuyama had even gone so far as to claim the “end of history.” Everything worth doing had already been done; all that Gen X kids had left to do was just coast. Or so it seemed. This zeitgeist was a recipe for cynicism, a prescription for disaffection. But it would get worse.

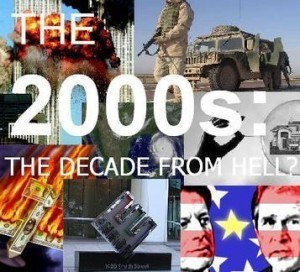

As the 1990s came to a close, and the new millennia dawned, this cynicism and disaffection turned into outright despair. The 9/11 terror attacks, the invasion of Iraq, and the establishment of the all-powerful surveillance state eroded what little faith remained in political institutions; and the economic collapses of 1999 and 2008 brought the fake prosperity of the 1990s to a shuddering halt.

It was clear that the Gen X cynics had every reason to be cynical, and that they knew they had been living on borrowed time. The general feelings of alienation in the air are on display in such films as The Matrix, Fight Club, and Being John Malkovich. Something was indeed brewing.

So the 2000s reaped the foul harvest of the 1990s. The economic collapse brought home the fact that the US was indeed a place of tremendous income disparity, where college graduates could barely expect to find a decent job upon graduation. The old men at the top, the “Baby Boomer” plunderers who pushed their own agendas for their own benefits, couldn’t have cared less about the young men whose nurturing was supposed to be their sacred duty.

The 2000s brought home the devastating reality that the 1980s and 1990s had been eras of irresponsibility, delusion, selfishness, greed, and unrelenting cowardice on the part of the government. Men could no longer ignore the fact that the jobs had dried up, the economy had hollowed out, their spoiled women had no sense of responsibility, and the popular culture derided them as beasts.

At the top, the super-rich classes could have cared less. They pushed socially destructive ideologies in order to line their pockets and fatten their purses. And the public interest be damned. They profited from cultural Marxism, feminism, marginalization of masculinity, and the destruction of gender roles. The goal was to turn the country into a compliant horde of consumer slaves. Values were jettisoned like used newspapers. Gen X-ers and millennials had been totally sold out by their forefathers, betrayed on the most basic level. It was a bitter reality, and one difficult to accept.

Meanwhile, in the popular culture, idealistic young men saw the growing domination of feminism, cultural relativism, and gay acceptance; as these forces advanced, traditional notions of masculinity became more and more marginalized. Never before had a generation of young men felt so marginalized and degraded.

And they had every reason to feel so. They were told by the popular culture that they were worthless, suspect, and defective. Their identity was not valued. And they sensed it.

All the conditions were in place for a furious backlash against the prevailing cultural conditions. And this backlash came with a vengeance. No one saw it coming. It came from the margins, and it came from the underground. But it is here now, and it is growing.

Faced with such adverse conditions, and with so many avenues now closed off to them, many men began to delve into self-improvement, seduction, physical fitness, and the forming of smaller “tribes” for mutual support. Gradually, these tribes began to adopt the list of themes identified in Roosh’s article.

It became clear that the way forward involved a blending of the old and the new. The traditional notions and values of “old school” masculinity needed to be renovated, or updated, by the new conditions of the 2000s.

The birth of a new movement

Thus was born the neomasculist ethic. It is a hybrid of old and new elements. The old elements are the traditional masculine virtues of the past: stoicism, the acceptance of brutal struggle, the solving of complex problems, the breaking through of barriers, the overcoming or conquering obstacles, the code of ethics of the good father and good brother, the rejection of degenerate or effeminate behavior, and the submerging of the personal identity in the pursuit of some altruistic goal. The new elements are simply the flexible, tactical means used to implement the older, traditional goals.

Neomasculinity employs new methods to achieve old aims. At its heart, neomasculinity is a corrective movement: it seeks to right the wrongs of our forefathers.

It is the masculinity of the new age, adapted to the current hostile environment that men now find themselves in. Neomasculinity is deeply conservative. It is a profound rejection of the false promises of the “liberalism” of the 1960s and 1970s. Men now recognize that the excessive license of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s set the stage for massive cultural decline, cultural bankruptcy, the erosion of masculine virtue, and economic collapse.

This selfish liberalism brought only the tyranny of cultural Marxism, feminism, and a general ethic of hedonistic depravity that counts every indulgence a positive good. It has proven to be deeply destructive to masculine (and even feminine) virtue.

But while neomasculinity rejects the “counter culture” nonsense of the 1960s and 70s, it also rejects the nihilism and despair of the 1990s and 2000s. Neomasculinity is action and hope, not resignation or despair. It is a deeply positive worldview. It accepts the fact that the way forward will be a hard one. It is a profoundly revolutionary ideal, and it seeks nothing less than the redefining of men’s role in Western society.

We will not shrink from our responsibility of promoting this ideal. We take up the torch that has been dropped by our forefathers. We will not apologize for our beliefs. We will not back down one inch. We will not prevaricate, and we will not hesitate. We welcome struggle and conflict, knowing our cause is a sacred one. Young men today accept the fact that, having been profoundly betrayed by their forefathers, they must shoulder the burden of restoring the ethic of masculinity to its rightful place.

They did not ask for this job. They did not want this job. But decades of cowardice, depravity, enervating cultural relativism, and overaggressive feminism have created a situation where men now see that their backs are up against a wall. If the masculine ethic is to survive, it will need to be defended. Blood has been spilled, and daggers are drawn.

Neomasculinity will fight, and will not stop fighting until the fight is done. And it will reclaim its rightful position as a force for social good.

Read More: Sharpen Your Tribal Instincts

Leave a Reply