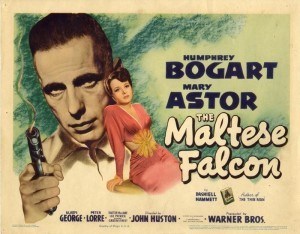

I am not generally a fan of old movies. The acting styles, set designs, plot artifices, and production values usually do not attract me. But there are some exceptions. One of these is the 1941 film The Maltese Falcon; its ethic and philosophy of life is directly relevant to men today, and is worth repeated viewing. We will discuss some of the reasons here.

In the 1940s, a new genre of film began quietly to make an appearance in Hollywood. It was a hard-bitten type of film, born of the cynicism and dislocation of the Second World War and its aftermath. This genre—which later came to be called film noir—came to be defined by its embrace of the following themes, in one form or another:

1. Men are prisoners of their nature. No matter how hard you try, you can’t escape your past or your character.

2. Crime sometimes does pay. Even when it doesn’t, the temporary thrills are worth something.

3. Women are unstable and inherently untrustworthy.

4. Most people lie or are treacherous.

5. A man must live by a code of honor, despite all the crookedness swirling around him.

6. Alienation from society is the inevitable consequence of living by a code of honor.

Recognize these themes? I thought so. You might call the film noir ethos the original “red pill” ethos. Film historians tell us that the “classic” period of noir spanned the 1940s and 1950s; after that, the genre fell out of favor, but never entirely died. It saw a major revival in the 1990s under the term “neo-noir” which continues to this day. I certainly have my own list of noir favorites, which I think every man interested in movies should see.

Film scholars also tell us that first of the genre was The Maltese Falcon (1941). Adapted from the Dashiell Hammet’s unrelenting grim crime novel, this John Huston production set a standard that few of its descendants have matched. It is a remarkable film: a misanthropic, dark meditation on human greed, the futility of effort, and the consequences of betrayal. In many ways, it is more of a stage play than a film.

Euripides would have liked The Maltese Falcon.

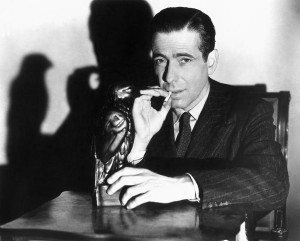

It is claustrophobic and oppressive, with all of the action taking place in hotel rooms and offices. Every character is either corrupt, an opportunist, or a liar, and their scheming machinations add to the oppressive atmosphere. Everyone is trying to screw everyone else; only Sam Spade, played wonderfully by Humphrey Bogart, is able to convey some sort of stoic honor.

The plot: an apparent damsel in distress (Mary Astor) visits private detective Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) to ask for his protection. Spade’s partner Miles Archer gets shot in the back while working on the case. The cops, apparently aware that Spade had had an affair with Miles’s wife, finger Spade as a murder suspect.

Spade is visited by a series of strange characters: Joel Cairo (masterfully played by Peter Lorre), the sinister Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet), and even his apparent client Mary Astor, who proves to be a master of deceit. Everyone is lying, everyone is concealing something, and everyone is trying to screw everyone else.

Slowly, the connections between all the characters are revealed. They are all engaged on a joint quest to find a precious artifact, a jewel-encrusted statute of a falcon, once in the possession of the Knights of Malta. Spade is skeptical, and apparently is motivated only by money. Or so he wishes everyone to believe. Feelings between him and Mary Astor begin to develop. Or do they?

The conclusion of the film is what enables it to rise above the cheap conventions of the standard crime drama. The quest for the precious statue turns out to be an illusion, a fools’ errand that brings its seekers only misery. It is the essence of the futility of effort, which would become a pervasive noir theme.

The cops turn out to be deluded, corrupt fools. The male supporting characters are scheming sociopaths. The only female character turns out to be a lying, manipulative murderess.

When Spade discovers that his partner had been gunned down by the woman he loves, he must put his allegiance to his moral code above his amorous impulses. “When your partner is killed,” Spade growls, “You’re supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t matter whether you liked him or not. You’re supposed to do something about it.”

Your comrades and your code are more important than your physical gratification. It is a lesson that many of us, in this age of simps, manginas, and white knights, have forgotten.

“You’re supposed to do something about it.” And he does. Despite all the rottenness of the world, despite all of its corruption and evil (or maybe because of it) a man of honor must be true to his own code. He must do the right thing in the midst of all the iniquity, in spite of all the swirling malevolence around him. Only this stoic courage is able to give life meaning.

The original book was chosen recently as a selection for the Wall Street Journal Book Club. Some readers were disturbed. According to its critics, the book is misogynistic, homophobic (in its portrayal of Joel Cairo), and amoral. In short, the same criticisms that are heaped on every work of art (yes, I consider The Maltese Falcon to be art) that makes certain people uncomfortable.

Ignore these namby-pamby voices. The Maltese Falcon has much to teach about life and human nature. As we go through life, we quickly find out that peoples’ motivations are usually not altruistic; that many women do rely on cunning and guile to manipulate men; and that most other men are craven and corrupt.

The only safe refuge, apparently, is to adopt a patina of detached irony. Spade shields himself from the evil of the world by his tough-guy exterior, but beneath that, we could say that he is a profoundly moral man. He sets things right with the case, avenges his fallen comrade Miles, and exposes the statute of the bird for the phony it is. Sam Spade is indeed a man of honor, if a flawed one.

This is a film that bears frequent viewings. Its message resonates just as loudly today as it did in 1941, surely one of the most fateful years in recent world history. Be skeptical of the world, and on your guard with strangers.

But never abandon yourself to despair, or your soul to amorality.

Read More: The Antimans

Leave a Reply