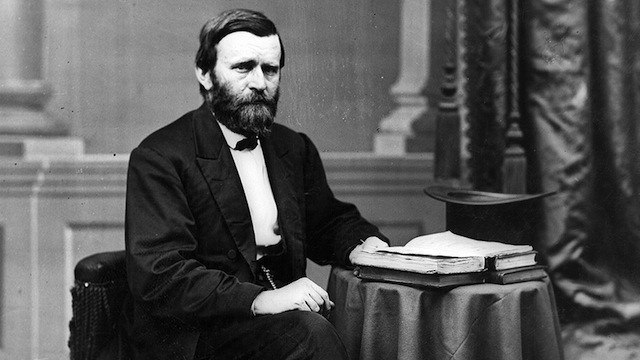

Ulysses S. Grant left his second term of office as president of the United States in 1877 with his reputation somewhat tarnished, but nevertheless intact. He had occupied the office during one of America’s fervent periods of expansion and concentration of wealth; and the consequential corruption that this expansion engendered had left a prominent mark on his presidency.

While personally honest himself, Grant was a product of the closed world of the military, where the grasping for money and power was more subdued than in the civilian world. He was a battlefield general without peer, but proved himself to be far too trusting, and unable to cope with the shark-infested waters of Washington and Wall Street.

He and his wife Julia then embarked on a “world tour” that would keep them in the public eye, and deplete their savings, for another two years. It must be remembered that in this era, there were no lavish speaking fees for ex-presidents; there were no think-tank directorships, no plum appointments, no lucrative book deals, and no lecture circuits.

Presidents had historically always been independently wealthy. Grant had amassed little wealth during his time in office, and in his day there was no pension for departing ex-presidents. Worse still, there existed a rule stating that military officers had to surrender their pensions if they wished to run for political office. So Grant had had to give up that safety net as well.

Thus Grant found himself in the unenviable position, after concluding his world tour, of trying to find ways of making money as a man of fifty-seven with a wife and dependents to feed. His greatest asset was his name: Grant was enormously popular with the public, and his unassuming manner and keen mind made a deep impression on all who met him. Otto von Bismarck, meeting Grant in Germany during his world tour, had been impressed with his American guest’s perceptive mind and quiet confidence.

Grant, frankly, lacked an aptitude for business. He had little sense of money and how it operated, and he was far too trusting when dealing with associates and employees. Worse still, there is little evidence that he was aware of this personal limitation; he should have sought out honorary positions in universities (as did his ex-Confederate counterpart Robert E. Lee) where his name and prestige would have been sufficient consideration for any salary received.

Alas, Grant chose to plunge into the worlds of business and high finance, with all of its attendant risks. These were activities to which he was quite ill-suited.

Grant, financier Jay Gould, and a former Mexican government official named Matias Romero pooled their resources in the early 1880s to found the “Mexican Southern Railroad.” The railroad might have benefitted from the favorable economic climate of the time, but the failure of Congress to implement a free trade agreement with Mexico doomed the venture. The railroad venture ended in bankruptcy in 1884.

But worse events were still to come. In 1883 Grant had been convinced by his son (Ulysses Jr), and his son’s friend, Ferdinand Ward, to start a Wall Street brokerage house. Ward was considered a financial maverick at the time, and promoted himself as the “Napoleon of finance.” He had enough panache and apparent success to seduce the Grant family; on Ward’s assurances, Grant invested over $100,000 of his own money in the venture. This was a huge amount for any man in the early 1880s, and represented just about all of Grant’s life savings.

Grant himself was not expected to do very much at the offices of Grant & Ward. He had been asked to join because the prestige of his name might attract potential clients. So Grant showed up at his office on Wall Street several times per week, smoking cigars and meeting prominent businessmen. He had long cultivated a serious smoking habit: author Charles B. Flood, in his work Grant’s Final Victory, claims that the ex-president consumed twenty-five Cuban cigars per day.

What the Grants did not know was that Ferdinand Ward was running a Ponzi scheme right under their noses. Ward provided his business partners with fraudulent information and “cooked” books so that the nature of his activities might remain undetected. He would entice investors to give him money, and then illegally use that money as “collateral” for multiple loans. “Investment dividends” were paid out regularly to give the impression of successful management, but this money was simply contributions from other investors. Ward, quite simply, was the Bernard Madoff of the 1880s.

Like all Ponzi schemes, Grant & Ward would eventually collapse. When first told of the news that Grant & Ward had imploded, Grant was in disbelief. He was left literally penniless. He discovered that he did not even own his own house: the payment of his mortgage had been entrusted to Ward, who had used it for himself. Grant, in despair, at one point even thought of killing Ward, but later stated he had no desire to be imprisoned for murdering so odious a creature.

It would not be long before personal tragedy of another sort would enter the picture. In 1884 Grant had seen his doctor, after complaining of soreness in the throat that would not go away. His physician took a tissue sample from the back of Grant’s throat, and had the sample examined; the growth proved to be cancerous. The lab technician informed Grant’s doctor that “he [Grant] was doomed.”

With his back up against the wall, and with his time on earth rapidly drawing to a close, Grant steeled himself for one last campaign that might provide for his family after his demise. He accepted an offer from the editor of Century Magazine, Robert Johnson, to write a book of personal memoirs.

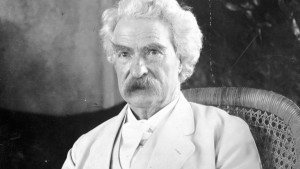

Similar projects by other Civil War figures had been moderately successful, and with the deaths of Lincoln and Robert E. Lee, Grant himself was the last of the major living figures of the war. Good luck also came from an unexpected source: Grant’s canny friend Mark Twain was able to negotiate very favorable royalty terms with the publisher on his behalf.

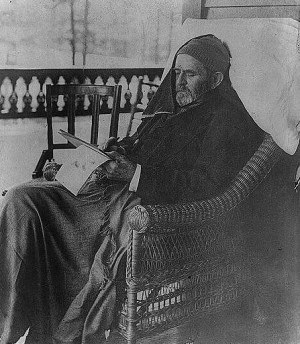

All through 1884, then, Grant toiled day and night on his book. During this time, cancer rapidly consumed his body. He was unable to eat anything except the most liquid of foods, and the act of drinking water “was pure agony” akin to “drinking molten lead.”

He did have several assistants to help him with the acquisition of materials and the checking of facts. Yet this was no ghost-written memoir, but the line-by-line product of Grant himself. He was not naturally a literary man, but his prose has a terse and dignified tone that strikes precisely the right chord for a book of this type.

The end closed in quickly. He died on July 23, 1885, only four days after completing the manuscript. It was an incredible feat of willpower and endurance. The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant was an immediate bestseller, and solved forever the financial problems of the Grant family. Its stature as a historical document and as a work of literature has held steady over the years, and is worth reading even today.

It was Grant’s last campaign, and the most personal of his victories.

Read More: Origins Of Neomasculinity

Leave a Reply