This article was originally published on Fortress of the Mind.

We take it for granted today that we should be able to think and speak as we wish. It is very easy to forget that this right has been the exception, and not the rule, for most of recorded history. It is a quite recent development. At one stage of history, the struggle to assert freedom of thought was bound up with the fight for freedom of religion: that is, the idea that a person should be able to worship as he pleased.

At later stages of history, the fight to assert freedom of thought and speech was bound up with political and social struggles. Whatever form it took, the quest was always the same: the desire to be free from retaliation while asserting one’s personal rights.

It will be useful to draw a general sketch on how freedom of thought developed. It is very important that we do this. For it will enable us to appreciate our current situation much better, and show us how it was the end result of a long, and even bloody, struggle.

Our story must begin with the ancient Greeks of the Ionian islands. For it was they who first bequeathed to history this most precious gift. There were many societies more ancient than they: Egyptians, Cretans, Assyrians, Chinese, Indians, and a few others. But in all of these societies–without exception, as it turns out–intellectual activity was kept firmly in the hands of the priestly classes, or in the hands of the monarchy.

Egypt presents a typical case. Only priests were taught the secret of reading and writing; we note that hieroglyphic writing died out so thoroughly because knowledge of it was in the hands of so few. The same situation existed in Assyria and India as well. In China, entry into the privileged classes was controlled by a formidable examination system. These societies were also rigidly stratified. No one outside the clergies or royal courts had much time or inclination for intellectual activity.

But something miraculous happened in early Greece. Perhaps it had something to do with the climate, the geography, or the fact that the Greeks had frequent contact with other cultures: Phoenicians, Persians, Cretans, and barbarians. Perhaps this intercourse stimulated them and caused them to question everything. Or maybe it was the fact that they were a trading and commercial people, who rebelled against the idea of control by despots.

Whatever the cause, it was a real and lasting development for European history. Philosophy and natural science (the two were one at this time) took shape with thinkers like Democritus, Thales of Miletus, Heraclitus, Anaximander, and many others. We know little more than the names of most of them. Diogenes Laertius’s Lives of the Philosophers contains many stories and short summaries of most of the pre-Socratic philosophers. It is well worth reading.

What matters is that these thinkers did something no one (as far as we know) had done before. They had the courage to question the established and inherited wisdom. They had the vision to ask “why?” about nearly everything. Nothing was forbidden: government, human relations, material substances, spiritualism, the existence of God, anything.

No central government or divine sovereign sought to muzzle them, except in very rare cases (that of Socrates being one). Reason and speech were truly free, and the result was the greatest explosion of creative activity the world had yet seen. Art, literature, music, drama, science, and mathematics flourished.

With the advent of Rome, this situation generally persisted. The spark of independence went out with Rome’s conquest of Greece in 146 B.C., but for the most part, scholars and philosophers were left alone as long as they paid lip service fealty to the emperors in Rome. The Romans were actually quite tolerant of religious diversity. All over the empire, a myriad of cults and religions could be found: the Oriental “mystery” religions of Serapis, Isis, and Mithras were just few of a great many. All the emperors asked was that communities pay their tributes and erect a statue of the emperor as a sign of loyalty.

Things began to change with the advent of Christianity, however. It upset the tacit agreement of religious tolerance in the Empire. It was different from all the other religions, in fact. To the Romans, it was deeply subversive: it preached that the “end of the world” was at hand; that Christians should refuse military service; and, most crucially, that theirs was the only true religion. It was profoundly intolerant of other religions. And this was something new.

At first the Romans looked up on the Christians as harmless fanatics, as just another obscure offshoot sect of the perpetually rebellious Jews. The Jews were also looked upon by the Romans with suspicion for refusing to accept emperor-worship; but for the most part, the Jews kept to themselves, and were content to preserve their customs and traditions in peace. But the Christians were different. They proselytized aggressively, and this made them dangerous.

It is almost amusing to read the Roman official Pliny the Younger’s frustrations in dealing with the Christian fanatics that came before him. They would not cooperate with Rome. They were recalcitrant and unyielding. And in his letters to the Emperor Trajan, he gave vent to his anger at these upstarts.

When Christianity finally inherited the Empire, its victory was complete. It became the sole official religion, and promptly banned all others. “Religious toleration” as we know it today did not exist then. Pagan temples were closed; heretical beliefs were persecuted; and the Platonic Academy in Athens, operating for many centuries, was finally closed. The emperor Julian the Apostate’s feeble attempt to revive paganism during his reign was ineffective and doomed.

Reason would sleep for a thousand years. To understand why this was so, we must appreciate what Europe was like at the dawn of the Middle Ages (i.e., in late antiquity). Men had lived through chaos and disorder, and were profoundly disillusioned. The great empire of Rome, in existence for many hundreds of years, was shattered. Stability and prosperity gave way to violence and chaos. Men had little time for speculative activity or books. They preferred certainty and comfort to the fresh air of reason. And a highly structured religion (Christianity) gave this to them.

Human thought made little progress in the Middle Ages. Scientific inquiry that might contradict Christian theology was discouraged, even dangerous. But the stirrings of the Renaissance in fifteenth century Italy changed everything. Scholars rediscovered the glories of classical antiquity, and the brilliant classical spirit of questioning received knowledge. Greek and Latin manuscripts (some hidden for centuries) came to light which fired men’s imaginations.

Although the Italian humanists had a gentleman’s agreement with the Holy See not to attack Christian doctrines openly, there could be no going back to the old ways once the new discoveries had been made. The Inquisition in Spain and Italy could keep a lid on “deviant” thought for some time, but ultimately it was a losing battle.

But the modern concepts of “freedom of speech” and “freedom of thought” were the outgrowth of two historical periods: (1) the European religious wars following the Reformation, and (2) the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. They both had a profound significance on history.

The major lesson of the religious wars, as we can see in the agreement that ended the Thirty Years’ War (the Peace of Westphalia in 1648) was religious tolerance. Neither Protestants nor Catholics could exterminate each other, or forcibly convert each other; so they must learn to live with each other. Europe was exhausted, and had no other choice. But this realization came at a horrendous price in blood and treasure.

With the Enlightenment, which burned most brightly in France, official Church doctrine finally came under direct attack. The growth of scientific, geographical, and astronomical knowledge made this inevitable. Man began to realize that he was part of a vast world, that extended across many continents and nations; and if he looked at the sky, he discovered that his world was only one of countless millions in space. Biblical teachings came to be seen more as allegory than as literal fact as biblical textual criticism began to take shape. What was once considered infallible now came to be appreciated as a literary work of man.

And yet, as ecclesiastical authority waned, the power of the modern nation-state grew. In many cases, it just stepped into the Church’s shoes as the unquestioned authority. It became the new overlord. Control of printing, books, newspapers, and magazines became an important part of keeping the public under a firm hand.

The societies that some permitted freedom of thought (e.g., Holland and England) seemed to be better at innovating that those that did not. The connection between these two things (freedom of thought and economic success) could not be denied. As Spain and Italy declined in economic power, so rose England and Holland.

This lesson–that innovation and vitality is impossible without freedom of speech and thought–is what we must conclude from this brief overview. As John Stuart Mill has noted, the societies that permit it do well; and those that do not, stagnate and shrivel up.

It goes without saying that I think freedom of speech is something we should all be interested in. For me personally, the topic matters a great deal. Attorneys who practice law and represent clients are confronted almost daily by examples of injustice and abuses of power. In some situations, these abuses can shock the conscience of any fair-minded man. The attorney must then do his best to give his client a chance at justice, even when the client is an unpopular one. And as writer, I believe writers should be able to express their opinions without fear of retaliation, whether such retaliation is direct or indirect.

The enemies of freedom of thought and speech are two: fear and laziness. Most people are naturally lazy and refuse to exert any mental effort that imposes demands on them. Fear is an even more insidious evil. People instinctively recoil in fear when confronted with ideas that challenge their own. They see such new ideas as threats to themselves personally. It is an irrational response, but we should at least be aware that it exists.

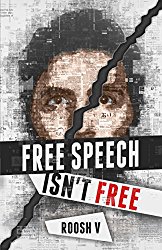

The writer Roosh Valizadeh (who is also a friend of mine) has just released an important book called Free Speech Isn’t Free. The book chronicles the story of his efforts to give a series of totally innocuous lectures in Canada last year, and relates the hysterical responses he received in opposition. I hope you will read it. His experience hammers home the point that freedom of thought is something that must be fought for.

Those who pull the levers of power in modern societies have all sorts of underhanded ways of suppressing or discouraging such freedom. It is our responsibility to be ever vigilant to such encroachments on our hard-won rights, and to call to account those who seek to abridge such freedoms.

It is supremely relevant for all of us, because in today’s world we will be confronted with those who lack any sense of justice, and who will wish to prevent us from expressing ourselves. To understand how such forces are emboldened and encouraged, we must learn from the example of others. Today it was Roosh Valizadeh; tomorrow, it could be anyone else. We have no excuse for not learning from history.

Freedom of thought is something worth fighting for. When we exercise this right, we finally begin to feel the intellectual bonds we share with those who came before us in history, and whom I have discussed above. Whether you agree with his opinions is irrelevant. The larger message is what matters; it resonates for anyone who seeks to advance a point of view in the marketplace of ideas without fear of violence or intimidation.

Those who seek to question the nature of things are part of a proud legacy, one that stretches all the way back to the Ionian shores; one that first began, perhaps, when a bearded Thales of Miletus looked at the world around him and began to ask the daring questions:

Why are things this way? And how did they come to be so?

If you like this article and are concerned about the future of the Western world, check out Roosh's book Free Speech Isn't Free. It gives an inside look to how the globalist establishment is attempting to marginalize masculine men with a leftist agenda that promotes censorship, feminism, and sterility. It also shares key knowledge and tools that you can use to defend yourself against social justice attacks. Click here to learn more about the book. Your support will help maintain our operation.

If you like this article and are concerned about the future of the Western world, check out Roosh's book Free Speech Isn't Free. It gives an inside look to how the globalist establishment is attempting to marginalize masculine men with a leftist agenda that promotes censorship, feminism, and sterility. It also shares key knowledge and tools that you can use to defend yourself against social justice attacks. Click here to learn more about the book. Your support will help maintain our operation.

Read More: 7 Deadly Sins Of Manhood

Leave a Reply