In part one of this series I proposed a model for women to skip the carousel and marry young, provided they can find a husband they are head over heels in love with and trust to lead them in life. In this post I’ll address the statistics around the common argument that young marriage leads to higher divorce rates because young women “don’t yet know who they are”.

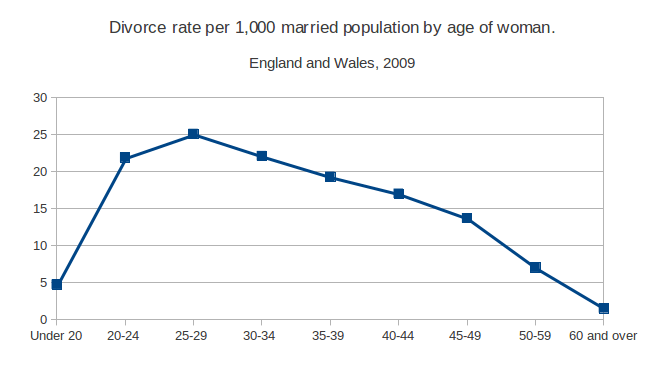

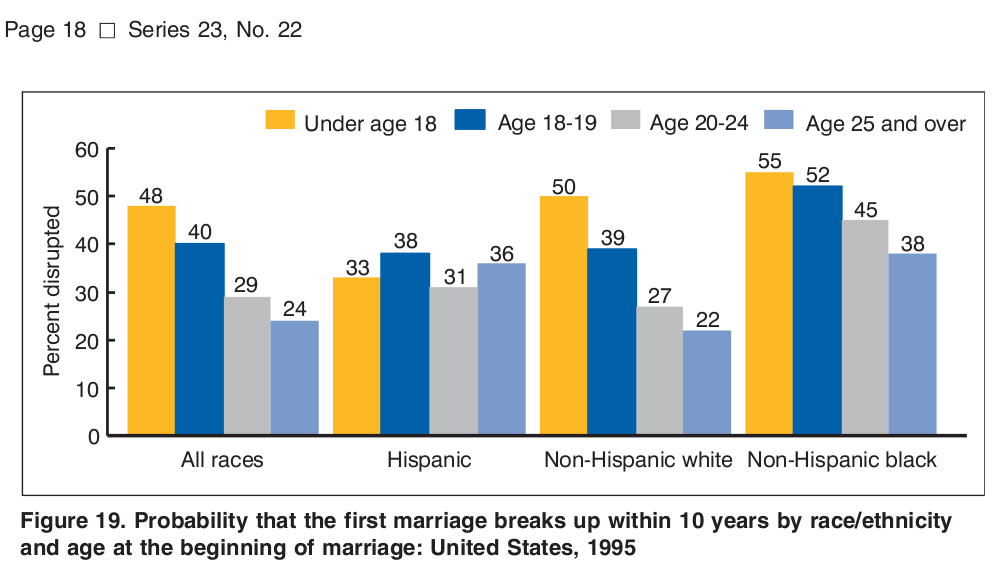

As you can see from the NCHS/CDC chart above, there is reason for concern here. Young marriages, especially very young marriages in that data set certainly do show a higher risk of divorce. However, this doesn’t necessarily mean that the higher divorce rate observed is due to women “not knowing themselves” yet. There are a number of plausible explanations, with that hypothesis being only one of them:

- Young marriage increases divorce risk because young women “don’t know who they are” yet.

- Women with higher IQs tend to go to college, and women who go to college tend to marry later. Given that IQ tends to negatively correlate with divorce, this could be what is actually being observed. See chapter 8 in Herrnstein and Murray’s The Bell Curve for a discussion of IQ, education, and divorce.

Edit: I quote from that chapter in this post. - Some percentage of young marriage (especially very young marriage) may be associated with impulsiveness, which itself would increase divorce rates.

- Divorce rates are highest when women are youngest and have the best chance of remarriage. Couples who marry when the wife is young are exposed to higher risk of divorce due to the wife being more attractive to other men.

My own sense is that all of these explanations are in play here to some degree. I’ll focus on the last hypothesis in this post and share the data I was able to find which may help shed some light on it. Before I share more data however, I think we need to consider some counter theories. These suggest that delayed marriage may in fact increase the risk of divorce:

- Women who delay marriage will generally end up with higher partner counts, which leads to lower marital satisfaction and greater risk of divorce. See The Social Pathologist’s Sexual History Divorce Risk II as well as his well known previous post on the topic.

- Marriage is a big change from single life. Women who marry younger have had less time to get used to being single and are more adaptable to the new lifestyle.

- Women who have become established and independent find it harder to accept their husband as the leader of the family. If they don’t see him as leading them, they are very likely to experience lessened sexual attraction and romantic love for him and become unhappy with their marriage.

Interestingly these counter theories aren’t actually disproved by the chart above. While the chart is dated 1995, this is the year the data source was compiled. To determine the 10 year divorce rate they must be looking at marriages which occurred in 1985 or earlier. In fact, this appears to be the same 1995 data set which I found looked at divorces going back to 1965 when looking at remarriage rates. This is important when considering what the 25 or over category looks like. The median age of marriage has been increasing over time, and if we are looking at marriages in the 60s, 70s, and early 80s we are looking at a time when the median age of marriage for women ranged from 20.5 to 23. So the 25 or over category in that study looks very different than first marriages in that category occuring today; it is skewed much more to marriages occurring in the woman’s late 20s.

Now lets return to the question of what causes marriages before age 25 to have higher divorce rates than marriages where the woman was just over 25. As I said, the standard explanation of women who marry young changing their priorities after marriage strikes me as having some merit. Under the current feminized model this would seem to pose a real risk, but my proposal in the previous post addresses that risk. I also think reasons two and three are fairly straightforward, and must be at least part of the explanation for what we are seeing. This leaves the final alternate explanation:

Young marriages are exposed to higher risk of divorce in the first 10 years because the wife’s chances of remarriage are highest when she is young.

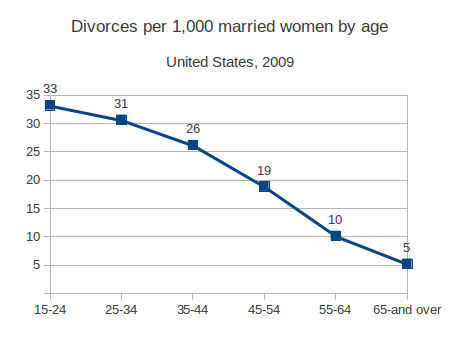

All else being equal, being married to a woman in her 20s is more risky than being married to her in her 30s, which is more risky than being married to her in her 40s, etc. The longer you move out the date of first marriage, the lower risk you will be exposed to (again, all else being equal).

However, this raises the question if all else really is equal. What if divorce risk in general is highest just after the wedding, and tapers off from there? This kind of trend might even explain the declining divorce risk as women age. Perhaps women aren’t motivated to divorce by their opportunity to remarry after all, despite common academic acceptance of the idea. Perhaps the chart above is just an artifact of divorce risk declining steadily the older the marriage gets. This question had me looking for more data to try to better understand what is going on. While I haven’t found any smoking gun one way or another, I have some charts which will shed some more light on the question.

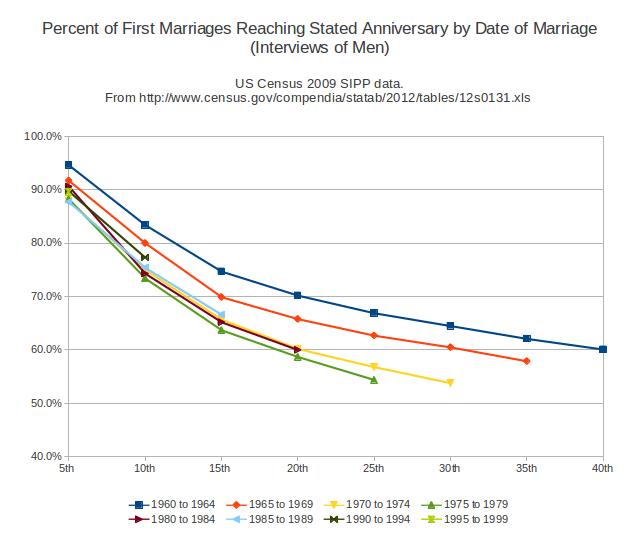

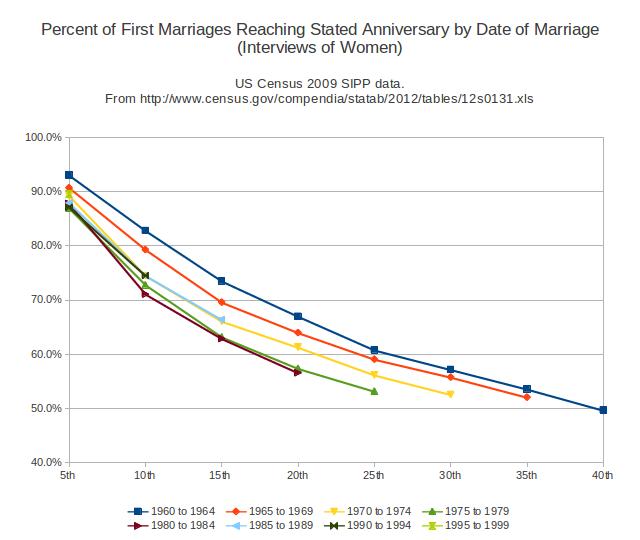

The chart above uses data from the 2012 Statistical Abstract of the United States, specifically from Table 131. They separate it out by men and women; the above chart is for men, and here is the same chart for women:

While the two charts are similar there is some difference. My best guess on the reason for this is deaths must be a portion of the reason marriages aren’t reaching the stated anniversary. Since husbands are more likely to pass away before their wives, more men who were interviewed had experienced long marriages than women. For this same reason, the results for men are likely a better fit when considering divorce risk since death of their spouse is less of a factor.

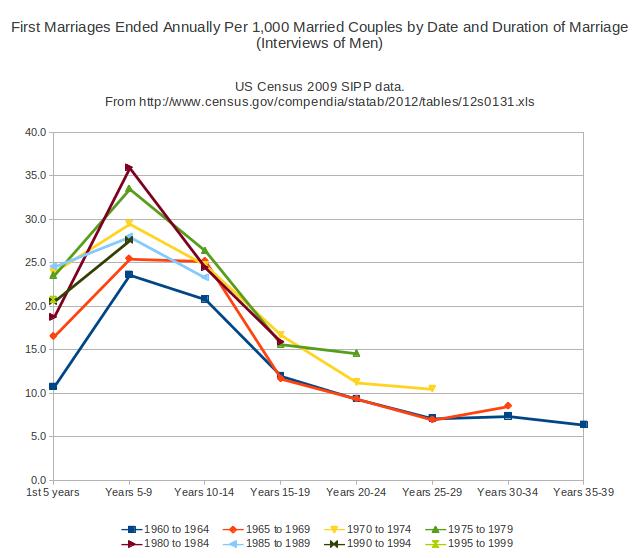

While these charts are the standard way I’ve seen this data displayed, they suffer from an important problem when trying to understand how divorce risk changes as the marriage progresses. The percentages are expressed in terms of the original group of marriages in the cohort, and therefore don’t account for the fact that fewer marriages exist in the later periods than in the former ones. Because of this, even if the divorce rate per 1,000 marriages was remaining steady throughout the duration of the marriage we would expect to see the slope of the curves decrease over time. To account for this I’ve reworked the same data to measure the number of marriages which disappeared during each period divided by the number of marriages the period started out with. I then took this number and divided it by 5 (the number of years in each period) and multiplied it by 1,000 to come up with a rough annual rate of marriage endings (death + divorce) per 1,000 couples. Here is what this looks like for men:

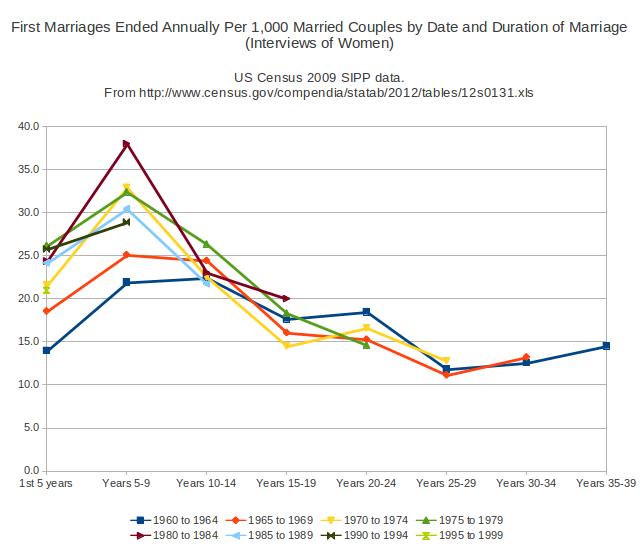

The pattern across marriage cohorts is strikingly similar. The risk of divorce jumps dramatically in years 5-9, and begins declining from there. There is a similar pattern for women, although you can see what appears to be the higher incidence of spousal death influencing the results:

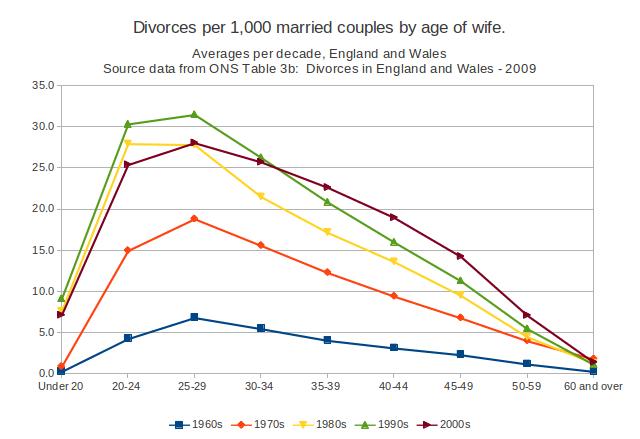

Overall the shape of these curves doesn’t fit with the hypothesis that the declining divorce rate as wives age is largely an artifact of risk changes due to longer marriages, at least in the US. However, it does seem to explain the peculiar shape of the UK curve:

Either way there is still the general question of which is the underlying cause of these trends. Does divorce risk decrease over time because only the strongest marriages survive? Or does divorce risk decrease over time because the wife’s temptation to divorce is lessened by her reduced opportunity to remarry? Given the way these are correlated I don’t think we will ever be able to prove exactly what is driving what. It makes sense to me that both of these are in play to some degree, but I do think that declining remarriage opportunities as wives age are a much larger driver of this trend than most people consider. Either way, what the data does prove is that the common bromides that divorce rates are up because lifetime marriage just lasts too long with our longer life expectancies and that divorce is driven by husbands trading their aging wives in for a younger model are pure nonsense.

Either way there is still the general question of which is the underlying cause of these trends. Does divorce risk decrease over time because only the strongest marriages survive? Or does divorce risk decrease over time because the wife’s temptation to divorce is lessened by her reduced opportunity to remarry? Given the way these are correlated I don’t think we will ever be able to prove exactly what is driving what. It makes sense to me that both of these are in play to some degree, but I do think that declining remarriage opportunities as wives age are a much larger driver of this trend than most people consider. Either way, what the data does prove is that the common bromides that divorce rates are up because lifetime marriage just lasts too long with our longer life expectancies and that divorce is driven by husbands trading their aging wives in for a younger model are pure nonsense.

While no smoking gun is likely to be found, I was still interested in better understanding how these things have changed over time. What has happened to divorce risk by wife’s age as women have continued to delay marriage? Has this increased the divorce risk for women in their late 20s and 30s? While I’m not aware of this kind of historical data for the US, the UK’s ONS does publish annual data going back to the late 1950s. I took the data from table 3b here and created averages for the last five decades:

While the general shapes of these curves have remained fairly consistent over the decades, there are some noteworthy changes between the 1990s and 2000s. Divorce rates in the UK for wives in their 20s dropped during this period. At the same time, divorce rates for wives in their early 30s remained the same while divorce rates for older wives increased. This can be interpreted as evidence that women delaying marriage while riding the carousel is starting to show up in divorce rates.

I don’t claim to have all of the answers here; hopefully someone will do a formal study on all of these questions. If you are aware of better data on this, I would appreciate you sharing what you have. Either way, the idea that young marriages inherently have uncompensated risk for divorce seems to be very much in question. If you understand the risk factors of impulsiveness and the benefits of higher IQ, and the woman is following the model I propose in part 1 I think you have an opportunity to significantly better your odds. Additionally, waiting to marry a woman who is older, more set in her ways, and has a higher partner count comes with its own set of risks, and this seems consistent with the last chart I shared for the UK. Much of the additional risk of marrying a young woman appears to come specifically from the fact that she is more beautiful and fertile and therefore has greater opportunity to remarry. With this in mind, waiting until your prospective wife isn’t as desirable isn’t a choice I think most men are likely to want to make. In that case, the risk itself comes with important compensation.

Note: I’ve put all of the related spreadsheet tabs I used to create these charts into one spreadsheet which you can now download. Please let me know if you find any errors in my work.

Leave a Reply