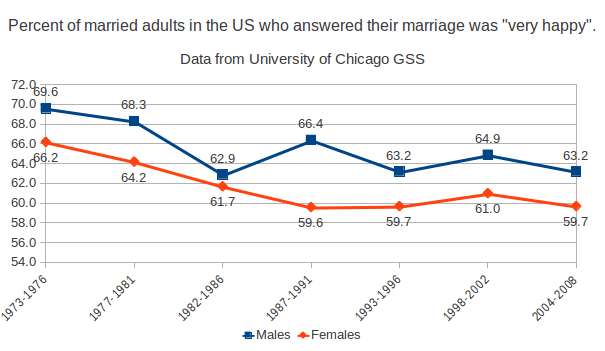

One of the most common and typically unchallenged assumptions about divorce is that despite all of the destruction it causes it at least makes people happier. Specifically, there is a feminist presumption that divorce makes women happier. Given the unfair nature of divorce laws and family court and the incentives the system offers to encourage women to divorce, this at first glance would seem like a reasonable assumption. Divorce should presumably drain off the most unhappy marriages, leaving the average married couple happier. But the data presented by the National Marriage Project (P 67 Fig 4) shows the opposite occurring:

Note that men and women were both happier with their marriages before feminists “fixed” marriage. This is especially surprising given the reduced social pressure for couples to marry following unexpected pregnancy. Abortion, readily available birth control, and acceptance of single motherhood have all but eliminated the “shotgun wedding”. In addition, with women having greater education and opportunity in the workforce they are under far less pressure to marry for economic reasons, as is borne out by the trend of women delaying marriage. Yet even with fewer presumably bad marriages entering the system and more unhappy ones exiting, married men and women are both less likely to report being very happy in their marriage. Something very powerful is clearly going on.

But this trend in itself isn’t proof that those who divorce aren’t made happier by it. What we need to evaluate is whether unhappily married people who divorce are happier than unhappily married people who choose to remain married. A team of sociologists lead by a professor from the University of Chicago has done this, and their findings destroy the conventional wisdom on divorce (press release and full study). From the Executive Summary:

But this trend in itself isn’t proof that those who divorce aren’t made happier by it. What we need to evaluate is whether unhappily married people who divorce are happier than unhappily married people who choose to remain married. A team of sociologists lead by a professor from the University of Chicago has done this, and their findings destroy the conventional wisdom on divorce (press release and full study). From the Executive Summary:

- Unhappily married adults who divorced or separated were no happier, on average, than unhappily married adults who stayed married. Even unhappy spouses who had divorced and remarried were no happier, on average, than unhappy spouses who stayed married. This was true even after controlling for race, age, gender, and income.

- Divorce did not reduce symptoms of depression for unhappily married adults, or raise their self-esteem, or increase their sense of mastery, on average, compared to unhappy spouses who stayed married. This was true even after controlling for race, age, gender, and income.

- The vast majority of divorces (74 percent) happened to adults who had been happily married five years previously. In this group, divorce was associated with dramatic declines in happiness and psychological well-being compared to those who stayed married.

- Unhappy marriages were less common than unhappy spouses. Three out of four unhappily married adults were married to someone who was happy with the marriage.

- Staying married did not typically trap unhappy spouses in violent relationships. Eighty-six percent of unhappily married adults reported no violence in their relationship (including 77 percent of unhappy spouses who later divorced or separated). Ninety-three percent of unhappy spouses who avoided divorce reported no violence in their marriage five years later.

- Two out of three unhappily married adults who avoided divorce or separation ended up happily married five years later. Just one out of five of unhappy spouses who divorced or separated had happily remarried in the same time period.

But could it be that those who choose to remain married are fundamentally different than those who choose divorce? They address this question directly:

Does this mean that most unhappy spouses who divorced would have ended up happily married if they had stuck with their marriages? We cannot say for sure. Unhappy spouses who divorced were younger, more likely to be employed and to have children in the home. They also had lower average household incomes than unhappy spouses who stayed married. But these differences were typically not large. In most respects, unhappy spouses who divorced and unhappy spouses who stayed married looked more similar than different (before the divorce) in terms of their psychological adjustment and family background.

One might assume, for example, that unhappy spouses who divorce and those who stay married are fundamentally two different groups; i.e., that the marriages that ended in divorce were much worse than those that survived. There is some evidence for this point of view. Unhappy spouses who divorced reported more conflict and were about twice as likely to report violence in their marriage than unhappy spouses who stayed married. However, marital violence occurred in only a minority of unhappy marriages: Twenty-one percent of unhappily married adults who divorced reported husband-to-wife violence compared to nine percent of unhappy spouses who stayed married.

Note that those who chose divorce were typically younger than those who stuck it out. Since we know that younger divorcées are far more likely than older ones to be able to remarry, the stats on the likelihood of the two groups to be happily married after 5 years (last bullet point above) are especially compelling.

So what was the secret of those who held it together to ultimately become more happy than had they divorced?

Many currently happily married spouses have had extended periods of marital unhappiness, often for quite serious reasons, including alcoholism, infidelity, verbal abuse, emotional neglect, depression, illness, and work reversals. Why did these marriages survive where other marriages did not? The marital endurance ethic appears to play a big role. Many spouses said that their marriages got happier, not because they and their partner resolved problems but because they stubbornly outlasted them. With time, they told us, many sources of conflict and distress eased. Spouses in this group also generally had a low opinion of the benefits of divorce, as well as friends and family members who supported the importance of staying married.

The secret to a happy marriage turns out to be extremely simple; stop thinking about divorce! This is why it is so critical to choose wisely when marrying. All marriages will run into rough waters; marriage will only work if both sides are fully committed to the institution. They also specifically tell us that marriage counseling wasn’t the solution:

The secret to a happy marriage turns out to be extremely simple; stop thinking about divorce! This is why it is so critical to choose wisely when marrying. All marriages will run into rough waters; marriage will only work if both sides are fully committed to the institution. They also specifically tell us that marriage counseling wasn’t the solution:

Spouses who turned their marriages around seldom reported that counseling played a key role. When husbands behaved badly, value-neutral counseling was not reported by any spouse to be helpful. Instead wives in these marriages appeared to seek outside help from others to pressure the husband to change his behavior. Men displayed a strong preference for religious counselors over secular counselors, in part because they believed these counselors would not encourage divorce.

Their finding that the secret to a happy marriage is in large part due to an unwillingness to entertain divorce has been corroborated in a separate study. This is also an observation which Terry Breathing Grace made in the comments section to a previous post:

Their finding that the secret to a happy marriage is in large part due to an unwillingness to entertain divorce has been corroborated in a separate study. This is also an observation which Terry Breathing Grace made in the comments section to a previous post:

Surely you agree that abuse notwithstanding, the standard must be that marriage is for keeps. I can only speak for my own relationship when I say this, but in our marriage, the absence of an easy exit has made the rough patches significantly shorter and farther apart than they would be if either of us had harbored fantasies of how much easier it would be if we threw in the towel.

It’s amazing how quickly you can see the good in your mate and understand that happiness comes from within when you know that the mate you have today is the one you’ll have tomorrow, barring the unexpected tragedy of death.

The basic premise is also born out by other studies of general happiness. Harvard psychology professor Dr. Daniel Gilbert has written about why not reconsidering one’s choice of spouse makes men and women happier with their marriages (H/T Dex):

The basic premise is also born out by other studies of general happiness. Harvard psychology professor Dr. Daniel Gilbert has written about why not reconsidering one’s choice of spouse makes men and women happier with their marriages (H/T Dex):

Consider the choice to marry one sweetheart over another. If you pick the genial, down-to-earth banker, will you forever regret letting go of that free-spirited artist who loves traveling as much as you? Probably not. The very fact that you’ll be living with — and experiencing — one spouse and not the other means that the passed-over option will quickly fade in your mind. “The people you don’t marry don’t move in with you,” says Gilbert.

Envisioning what life would have been like with an alternate spouse becomes difficult and increasingly irrelevant as you settle into the life you’ve selected. “Once you make a choice in life, the unchosen alternatives evaporate,” he says. According to Gilbert’s earlier research, which he featured in his 2006 book, Stumbling on Happiness, when faced with an irrevocable decision, people are happier with the outcome than when they have the opportunity to change their minds. “It’s a very powerful phenomenon,” he says. “This is really the difference between dating and marriage.”

This effect is removed however if one continues to reconsider the choice to remain married, as women are constantly encouraged to do:

But what if the person you didn’t marry moved in next door? Suddenly your attention isn’t completely collapsed on your own marriage, and every day you can witness the alternative life you overlooked.

The irony here is that the safety valve which feminists and others fought so hard for to avoid women being trapped in unhappy marriages has made women both less happily married and more likely to be unhappily divorced.

The escape route is the disaster.

Leave a Reply