Nature has granted us extensive powers to observe, and to draw inferences from those observations. For most of us, observations are blithely made and discarded, in the hundreds upon hundreds every day. Even if we make a significant observation, only rarely do we have the presence of mind to ask follow-up questions; and rarer still do we have the conviction to draw the ultimate conclusions from what we perceive. What separates the average man from the truly exceptional man is this: first, the latter will instantly recognize an important observation when he encounters it, and second, he will have the courage to probe into the implications of this observation, regardless of where his conclusions will lead him.

But is there anything more rare than this type of man?

Far, far too often, we censor ourselves, and we hold ourselves back. We timidly suppress our boldest observations out of fear of social opprobrium or the mockery of the herd. But there is nothing more awe-inspiring than the example of a man who is able to see something of importance which no others have recognized, who has the intelligence to ponder the observation, and who then possesses the moral courage to make devastating deductions in the face of popular resistance.

It is the power of the will, displayed in all its muscular radiance.

So the great French philosopher Rene Descartes, lying sick in his bed and watching the movement of flies on his ceiling, began to make inquiries which would lead to the development of analytic geometry; so Albert Einstein, bicycling through the Viennese countryside, began to think about what it would be like to ride on a wave of light; so the great astronomer Christian Huygens measured the relative distances between stars by peering at them through small hones drilled in brass plates; and so the Greek scientist Eratosthenes was able to make perhaps the most sublime and beautiful observation in all of geographic history.

We will discuss him and his greatest achievement now.

Eratosthenes (c. 275-195 B.C.) was a driven and brilliant scholar whose erudition on many fields earned him the position of rector of the Alexandrian Library during the reign of Ptolemy III. His rivals and jealous colleagues liked to tease him with the nicknames pentathlos and beta, for his distinction in many fields, while always supposedly being second (beta) best. But as we will see, he was anything but “beta”. By the age of forty, his list of achievements was already astounding. He was a paragon of Hellenistic learning.

He wrote a history (Chronographia) of the major events of Mediterranean history, a volume of verse, and even a history of comedy. As a mathematician and scientist, he discovered a mechanical method for finding mean proportions in continued proportion between two straight lines. He measured the “obliquity of the ecliptic” (an astronomical term related to the orbit of the Earth) to an error of only one half of one percent.

But he was anything but a narrow-minded bookworm. Alexandria in his day was perhaps the world’s most cosmopolitan city. Greek in culture, but international in population, it possessed large numbers of foreigners from all over the Near East and the Mediterranean world. Traveling frequently and conversing with merchants, traders, and military men, he was able to make his Geographica the most authoritative treatise on geography for several generations. Unlike many men of his era, he was free from ethnocentric chauvinism, and believed men should be judged only on their actions, not their country of origin. Many Persians and Hindus, he counseled his pupils, were more honest and refined than Greeks, kept their word more frequently than Greeks, and had a greater aptitude for good government and social order.

But his greatest achievement, and one that will forever be a classic example of the power of deduction from the most rudimentary tools, was his measurement of the Earth’s circumference. Like many achievements of genius, it is unsurpassed in its simplicity and profundity. Let us examine just how Eratosthenes achieved this feat, more than a thousand years before the European discovery of the New World.

In Alexandria, he chanced to read in a book (or overheard a colleague mention) that at noon on the annual summer solstice (June 21) the sun at the city of Syene shone directly over a well. Residents of Syene were able to see the bottom of the well illuminated from the rays of sunlight shining directly overhead. The illustration below shows the details.

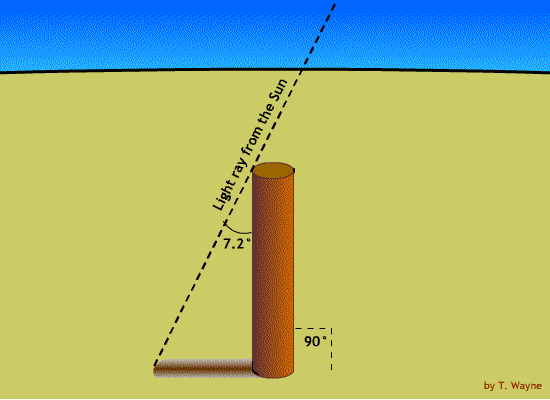

On June 21st of each year, the sun was directly overhead at Syene, but cast a shadow in Alexandria.

Now, this bit of information would have passed unnoticed through the ears or eyes of the average man. The solar illumination of the well in Syene had been going on for generations, and no one had ever given it the slightest thought. But Eratosthenes was not an ordinary man, and such men have the ability to take seemingly insignificant pieces of information and then use them to draw shattering conclusions. What he did next shows the analytic powers of the human mind at their very best.

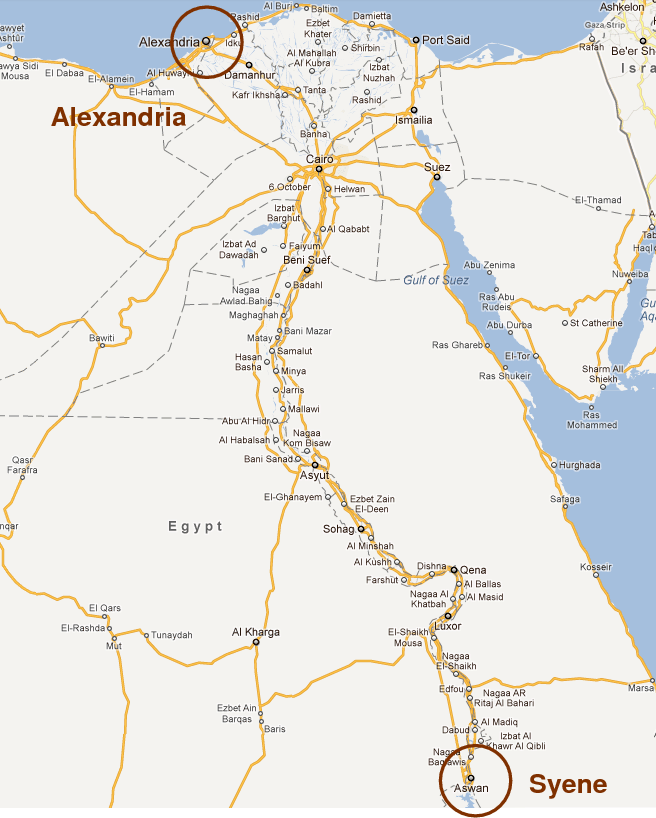

Map showing the distance between Alexandria and Syene in Egypt.

He asked himself a key question: why are no wells in Alexandria illuminated by overhead suns on the date of the summer solstice? What explanation could there be for this phenomena? Eratosthenes knew of the sphericity of the earth; it had been taken for granted by his predecessors Aristarchus and Hipparchus, and perhaps the idea even went back to the Babylonian astronomers. But none of his predecessors had the patience or conviction to follow their observations in a systematic way. Eratosthenes did, and achieved immortality.

He noted that on June 21 in Alexandria, an obelisk cast a shadow on the ground of 7.5 degrees from its apex. He measured the distance between Alexandria and Syene, finding it to be about 500 miles. In the diagram below, the letter “s” represents the distance between Alexandria and Syene.

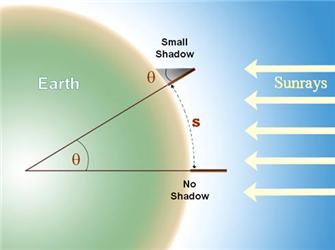

Diagram showing Eratosthenes’s experiment. The sun is so far away that its rays arrive parallel.

Putting this data together, he then sketched it out as a problem in geometry. The diagram below shows the well at Syene, the obelisk (or tower) at Alexandria, and the distance (represented by “s”) between the cities.

Since opposite interior angles are equal, the two angles represented by the letter theta are equal.

Now Eratosthenes knew from basic geometry that opposite interior angles are equal. Thus, if the angle of the tower’s shadow at Alexandria was 7.5 degrees, then the angle enclosing the arc of the circle from Alexandria to Syene must also be 7.5 degrees. The two angles represented by the Greek letter “theta”, in the diagram immediately above, are equal.

It followed from this that an arc of 7.5 degrees on the Earth’s circumference must equal 500 miles. And if 7.5 degrees equaled 500 miles, then, using simple logic, 360 degrees (a full circle) must correspond to about 24,000 miles.

This turns out to be very, very close to the correct answer. It was an amazing performance to draw such an immense conclusion from such a mundane observation. Observation: a well in another city is illuminated by the sun a certain day of the year. Conclusion: the circumference of the Earth is 24,000 miles. I love this story because it shows just how powerful a man’s will and conviction can be if it permits itself the freedom to soar.

It all seems so basic, so simple, in hindsight!

Except it isn’t. Great moments of inspiration always seem “easy” to achieve in hindsight. Especially when someone else has done the work. And such moments can come in very unexpected ways, as when Archimedes, immersing himself in water, discovered the principle underlying specific gravity. We all have such “eureka” moments, in one way or another. But who among us has the courage to act on them?

All of us have the power to observe. What we do with those observations is another matter. We can choose to ignore them, or to catalogue them away nicely, and refuse to act on the implications of our observations. If we have faith in ourselves, and if we have the courage of our convictions, we will approach the world with the fearless spirit of Eratosthenes. We live in a world where information is all around us: we can barely escape it. The problem of our era, and the challenge for us, is not so much finding information, but rather it is having the courage and conviction to act on what we know.

Act now. You already have made the observations. You already know the data, and you know the terrain. You are unlikely to know any more later than what you know now. Have faith in your own perception, and learn to trust your instinct. Take things one step further. One leap further, as Eratosthenes leaped. And an ocean of discovery, and perhaps even immortality, will await.

Read More: The Power Of Shame

Leave a Reply