A lot of red-pilling has been going on last years. Among normies, of course, as Trump’s victory and the Brexit showed, but also among the Right in the wide sense, especially concerning economics.

Many of us have been libertarians at one point. We were looking for an alternative to the ubiquitous Leftism, without straying too far from what we could explicitly stand for in a so-called polite society. Libertarianism showed up quite naturally. We were—and still are—oppressed by political correctness, burdened by excessive taxes and paperwork when starting new ventures: libertarianism promised us free speech, freedom to work, and no more burdening nanny State. To Americans, libertarianism also tends to mingle with the pioneers, that is, undoubtedly masculine men who could deal with the harshest situations and built a bright civilization on their own.

But then something happened. Some of us noticed that, in a free market, cunning and wealthy businessmen can swallow other companies, thus creating monopolies and gauging consumers through artificially inflated prices. Some noted that workers who accept a lower standard of living than others will bring their peers’ standards down through a tougher competition. Some pointed out that libertarianism is ultimately inefficient against Leftists, who can use their own classical liberal “rights” as a basis for their destructive efforts whereas negating ours, and against wealthy people or companies who fund Leftism.

Among us, specifically, it has been noted that the sexual marketplace has become more deregulated and that women sell themselves to the highest bidder at the expense of most men.

As to contribute to this brainstorming on economics, which sometimes gives truly brilliant results, I would like to dwell on something we know but often gloss over: the managerial State. Its advent in the US has coincided with blue, then most white collars getting screwed. Yet, a managerial State does not necessarily offshore employments, screw the middle classes and fund sluts.

Capitalism, Socialism, and the managerial State

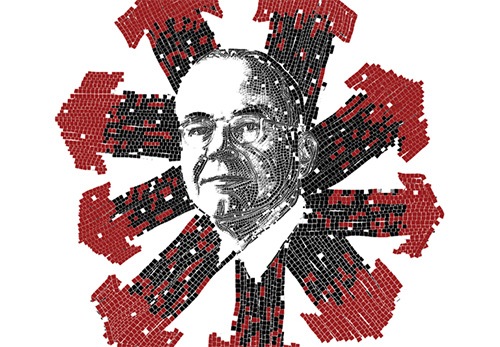

James Burnham

The first well-articulated description of the managerial State can be found in James Burnham’s The Managerial Revolution (1941). According to him, this kind of State—we’d call it “technocracy” in today’s language—is substantially different from both classical capitalism and socialism.

Capitalism means that capital property allows one to make money out of those who, having no such capital, need to sell their labor power to survive. Private property, as classical liberals theorized it, supports the idea that owning a factory or a company allows for reaping all its results—the payment of wages coming second and being subordinated, not to what one produces or merit, but to contracts and the owners’ goodwill.

Socialism sprang up in part as a reaction to the difficult condition of proletarian factory workers. Against the power of capital ownership, socialism stood up for the end of social classes, the sharing of work products, and an extended parliamentarianism allowing “the people” to have a voice in public debates. (I am just mentioning what socialism purported to defend in theory, not what actual socialists, or rather Marxists, did.)

By contrast, managerialism can actually arise from both. A manager can be a top dog in the corporate world, making millions out of his ability to coordinate the production of various departments, just as he can use the same methods as a civil servant. Right after the management sciences were born in the US, they have been eagerly imitated by the Bolsheviks—and Western bankers enthusiastically funded Soviet industry.

The efforts of these wealthy capitalists resulted in concentrating more and more power in their hands. From these heights, they felt the need to manage their power efficiently—thus feeling the same as Soviet plan commissioners. In the US, most of the economy has been absorbed by the corporate and banking behemoths, which makes very difficult to succeed as an independent: that absorption is equivalent to the USSR collectivization in that both rip small-scale independent properties from the hands of middle classes and put them under the sway of managers. Big State and Big Corp are run by like-minded men. Needless to add, defending one against the other is rather pointless.

If there is a struggle, it isn’t between capitalism and socialism, but between those who want a strong middle class—be it thanks to efficient trade unions or through the existence of a class of small independent producers, willing to stand for their prerogatives—and those who want to dissolve the middle class—either through open Statism or by turning previously independent producers or protected workers into precarious part-timers.

Burnham stressed how globalism would reflect the interests of the rising manager class. Managers perceive sovereignty, organic economy and institutions such as the family as impediments to their power. They would, thus, be naturally inclined towards the destruction of nations and institutions. Individuals ought to become more malleable to fit into the board of directors’ plans.

The managers’ Achilles heel

Sam Francis, one of Richard Spencer’s mentors, saw how the rise of feminism and “diversity” fit in the manager’s agenda:

[T]he managerial elite has a proclivity toward as well as a material interest in adopting and promoting ideologies of universalism, egalitarianism, cultural relativism, behaviorism, and “blank slate” environmental determinism… The ideological reconstruction of American society to suit the needs and interests of the emerging managerial class thus involved a repudiation of the older values, codes, and belief-systems of the old elite and a cultural conflict with those who continued to adhere to them.

Managers feel no loyalty towards their ethnic cousins, families or nations. When confronted with the consequences of their politics, comfy bureaucrats defend themselves with the so-called unavailability of “globalization”, which is a convenient excuse to keep pushing their class interest at the expense of most people. We are dispossessed because the Leftist establishment—managers and their “minority” pets—sucked up or destroyed what was rightfully ours.

Managers prosper through the hypertrophy of both public and financial sectors. HR are impeding the workers’ production, but managers won’t care, because they aim rather at control than wealth. As to the financial sector, remind that it does not directly produce any wealth but is essentially slave-racketeering as Samseau puts it. Financiers merely move money around for usury, low-wage work, and keeping the majority indebted.

Fortunately, the system is far from flawlessness. The most important flaw, I think, is that no matter the coldness and efficiency they try to project, managers are still human beings.

Take the Ivy League students for example. Outwards, they are winners, likely promised to brilliant careers in the Hollow Empire. Inwards, however, things are quite different. As a former Yale professor testified:

I have witnessed in many of my own students and heard from the hundreds of young people whom I have spoken with on campuses or who have written to me over the last few years…

Look beneath the façade of seamless well-adjustment, and what you often find are toxic levels of fear, anxiety, and depression, of emptiness and aimlessness and isolation. A large-scale survey of college freshmen recently found that self-reports of emotional well-being have fallen to their lowest level in the study’s 25-year history.

So extreme are the admission standards now that kids who manage to get into elite colleges have, by definition, never experienced anything but success. The prospect of not being successful terrifies them, disorients them. The cost of falling short, even temporarily, becomes not merely practical, but existential.

Having turned the social world into a pool of hapless, atomized, malleable individuals, managers got a taste of their own medicine: they are together alone, no one being loyal to anyone else beyond fleeting interests—that always end up creating new rivalries.

[The managerial class] is increasingly defined by neuroticism, insecurity, petty status competition, and a lack of intellectual foresight. In other words, the managerial class is composed of high-performing drones who are constantly fretting about losing their coveted positions and work even harder for the system that keeps them ensnared. (Source)

Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World envisioned a world where children would be growing up in incubators and taken care of by public institutions. We are already there. More and more children are born through surrogacy so that rich gay couples can play doll with them, and most children are “educated” by TV and a dumbed-down school system. Does this system produce happy people? The answer is a resounding no—even among managers.

Aside from those who kept the sense of family, managers have no other safety net than money. Aging, childless female careerists start chasing young men, and no matter how socially successful they may sometimes be, they will never be happy, as they failed to fulfill their true destiny.

All this is good news. The gap between managerial State logic and what managers as human beings need—kinship, thick social relationships, family—means that such an unnatural condition cannot last forever. The System cannot give more to its atomized managers than money, empty fashions and deep solitude. Thus, individual managers who discover the root of their perpetual dissatisfaction and existential distress may start leaning on our side.

And you, my little girl, constantly switching partners

When you’re doing something foolish, your salvation is abortion

But some mornings you just wake up crying

After you dreamt all night of a big table surrounded with children

Is the managerial State always an enemy?

“Throw it in the fire!”

“No Sam. The ring is mine.”

But wait a minute. So far I talked about the managerial State as an enemy. I had to, because its rising in the US and everywhere after 1945 impacted badly on most of us. Yet it isn’t necessarily so. In fact, a managerial State can aim at defending its own people, the nation’s culture, or the family and traditional sex roles.

How does Trump repatriate jobs? He negotiates with big companies, along with a favourable power balance, so that they close their offshore sweatshops and run anew American factories. This isn’t capitalism, since capitalism in the strict sense forbids such interventionist policies. This isn’t socialism either since it has nothing to do with more parliamentarism or destroying social classes. Rather, Trump’s policy is a managerialism that aims at protecting American citizens.

A managerial State ran by GloboCorp, Jews and pathological individuals such as family-hating lesbians is an enemy. It will aim at stripping us from our jobs, our autonomy, our ability to create and sustain families. But what about a managerial State ran by vastly different individuals, that aim at protecting the majority, the family, and at dismantling cultural Marxism?

On the one hand, a new managerialism is both possible and necessary. In the aftermath of Trump’s election, red-pilled men should join the new administration, create formal or informal power networks, reconquer bulwarks and dismantle the Leftist establishment. Of course, such managers should be loyal to masculinity, to their kin, to the values most of us already share. Perhaps, in the long run, they should aim to grow anew an organic economy, even if this curtails their own power as managers.

This is much easier said than done. Remember how the Lord of the Rings ends? When Frodo reaches the top of Mount Doom, right upwards a stream of the only lava that can destroy the maleficent ring, he backs down. Sam urges him to throw the ring into the lava. Frodo should. He accepted this as his mission, and he went through an incredibly arduous journey to do so. But even then, the power corrupts, and Frodo tries to keep it before Gollum providentially causes its fall.

Wouldn’t “our” managers be too tempted to identify as a class, with separate interests, and turn against us later?

We need, undoubtedly, to push red-pilled men in positions of power. The question of their loyalty is at best a future issue. Still, I think it is worth keeping on the back of our heads, especially since some on the Alt-Lite have already succumbed to the temptation.

Read Next: The American Elite Hates America

Leave a Reply