There is a perception that “education” involves stuffing one’s head with facts and information. What passes for male education these days is a sad mockery of the word, for it places far too much emphasis on intellectual development and attaches too little importance to the training of character. The cultivation of leadership qualities in men is a critical component of character building, and yet the idea that it should be taught systematically has nearly vanished from organized education.

One could argue that what young men today lack the most is vigorous training in character and leadership. Instead, curricula have been inundated with political correctness, timidity, gender sensitivity, and concerns for not hurting women’s feelings.

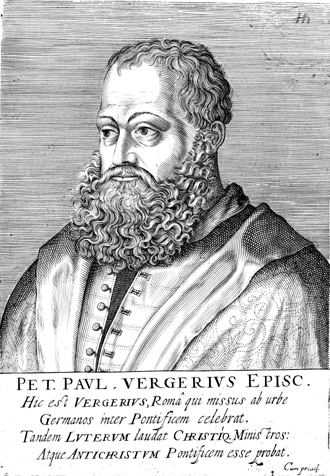

Many of the modern man’s problems—unrelenting simping, lack of inner game, lack of confidence, catty behavior towards other men, dissipation of focus and intensity, weakness of mind or body—can be attributed to the gross deficiencies of our educational system, as well as to the complete lack of mentorship for young men. It was not always so. This article will discuss the educational views of an influential Italian humanist named Pier Paolo Vergerio as expressed in his treatise The Character and Studies Befitting a Free-Born Youth.

Born in 1370 in Capodistria (what is today the city of Koper, in Slovenia), Vergerio taught rhetoric and law in Padua, Florence, and Bologna, and served for a time as an advisor to the Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund. His educational essay for men, composed around 1402, is a near-perfect summary of the Renaissance idea of education for young leaders. It was published numerous times in the following centuries, and had considerable influence. It is a pity (though not surprising) that it is not more widely known today. For nearly alone among his contemporaries, Vergerio was a firm proponent of the idea that everyone has different talents, and that an educational program must be adapted to each student’s strengths and weaknesses.

Bird’s eye view of Vergerio’s birthplace of Koper, in Slovenia.

I have culled Vergerio’s main points from his essay, and present them below. I then offer my own comment.

1. Education in character begins in the cradle. Parents should pick a name for a boy that is not “unseemly” or clownish. The correct choice of name is a matter of high importance, despite the cavalier manner with which most women treat it. Names can affect character and influence the career choices for men, and nothing is worse than being saddled with an oafish name.

2. Parents should settle their sons in “renowned cities” (in egregibus urbibus). Few opportunities will be found in the middle of nowhere, and men need the company of other good men to develop themselves.

3. Although training in the liberal arts should start at an early age, parents should take care to direct sons to those studies for which they are naturally inclined. Compulsion in education is something that should be used in careful moderation.

4. Body and mind are connected intimately. Just as a healthy body consumes and digests food well, so a healthy mind will not scorn anyone, but will put the best interpretation on what it hears or learns.

5. Young men should look at themselves in the mirror often. There is nothing wrong with this, and it serves a useful function. Those with a fine appearance will not dishonor themselves with vices, and those with an average or ugly appearance will strive to make themselves more attractive with their virtues.

6. Young men are generous and open-minded by nature because they have rarely experienced want and need. They are also credulous, due to their lack of worldly experience. Their opinions can change easily and quickly. They take great pleasure in their friendships and love the clubs they belong to, which they often “join and abandon on the same day”. Leadership instruction must be given while taking into account these qualities.

7. Every age of a man’s life has vices particular to it: adolescence “burns with lust”, middle age is “rocked with ambition”, and old age “wastes away in greed”. Not everyone is this way, but men are more inclined to these vices according to their age.

Another view of the city of Koper.

8. Young men must be taught from an early age to treat the elderly with “profound reverence”. Much can be learned from a young man’s associating with an older man. So Roman youth treated senators and other older men, thereby learning much about perseverance and patience.

9. Young men should learn right away the value of being constructively criticized and admonished. This is necessary for personal improvement. People who don’t listen to anything they dislike are “the ones most vulnerable to deception”. The weak stomach is the one that “will only accept delicacies.”

10. Excessive leniency can corrupt a young man. Women are unsuited to the task of training a man for male leadership. Those who have been “brought up in luxury under widowed mothers” display these negative traits most openly. However, this problem is easily corrected provided the proper male role models appear, one way or another.

11. The finest studies for leadership are those based on arms (military) and letters (history, philosophy, languages, and rhetoric). Everyone wants to be learned in old age, but to achieve this one must start early and exert “zealous effort”. Being learned in letters and arms will provide a remedy against “sloth” and solace in the face of worry and stress.

12. The ancient Greeks trained young leaders by teaching letters, wrestling, music, and drawing. This sort of regimen gave them appreciation for the “beauty and charm of things both natural and artificial”. “Great men”, he says, “need to be able to talk among themselves and make judgments about matters of this kind”.

13. Good disciplines to know also are literature, in that it forms good habits of virtue, and strengthens the memory by study. Rhetoric (the art of eloquence) and disputation are required also for being able to verbally spar with opponents in the inevitable contests that will confront any leader. Poetics is good for relaxation, mathematics and the sciences good for logical development, and languages for getting outside oneself.

14. Don’t just dip into any authors. Surround yourself only with the very best. By keeping company with great men, we will learn greatness by association. The most important quality in education is hunger: that fanatical desire to learn and better oneself. Some students have it, some do not.

15. The easiest person to deceive is ourselves, and no one who is damaged more than ourselves by such deceit. Young men must confer often with peers and guides, so as not to form an inflated opinion of themselves.

16. The training of the body is of paramount importance. It should be conditioned from a young age for rigorous service, military ability, and endurance. Young men should be hardened from a young age to endure pain and discomfort of all sorts, so that they are not broken by the strains of life and struggle. They should also be taught to “dare great things”. The Cretans and Spartans valued hunting, running, wrestling, and jumping, and sought ways to train themselves to endure hunger, thirst, cold, and heat. Luxuries weaken the mind and body.

Cultivation of the martial virtues is an essential part of leadership training.

17. In a great quote, Vergerio reminds us that “Every period of life has the capacity to yield something splendid.”

18. The youth should set fixed hours for bodily exercise every day, and fixed hours for the exercise of the mind. Strict self-discipline is critical. The emperor Theodosius, he notes, would engage in military exercises or legal judgments by day, and by night would apply himself to his studies by lamplight.

19. Since battle tactics are constantly changing, a forward thinking youth will attempt to master the martial arts and self-defense arts of his day. This should include mastery of weaponry, personal combat skills, horsemanship, and movement over rugged terrain carrying heavy loads or equipment. There are many different kinds of combat. “For things are done one way in a melee; another when the decision rests on a battle formation; another when there is an infantry charge, and another when combat takes the form of a duel.”

20. Expect often to be unfairly judged. Generals get the praise for the valor of their soldiers, but also get scorn for their shortcomings. “The glory that comes from good deeds is unequal to the shame that comes from mistakes”.

21. Learn to swim well. It greatly increases confidence.

22. Rest and leisure is of vital importance. Hunting, team sports, and fishing “refresh the spirit with great delight, and the movement they require fortifies the limbs.”

23. Dancing and cavorting with women is also essential, and there is a “certain profit in doing them, since they exercise the body and bring dexterity to the limbs, if they do not make young men lustful and vain, corrupting good behavior”.

24. From time to time, however, “one needs to do absolutely nothing and be entirely free from work, so as to meet once again the demands of work and toil. For the muscle which is always stretched taut usually breaks if it is not sometimes relaxed”.

25. Grooming the body is critically important. The end result should be neither “too fastidious nor too slovenly”. Excessive focus on grooming is “a sign of a feminine mind and a proof of great vanity”.

Final Thoughts

All in all, this advice is an excellent program for training in leadership and character. For a short treatise, this little work can scarcely be improved on. Vergerio’s counsel was directed at individuals, but we should note that masculine virtue does not exist in isolation. It thrives only when certain conditions are met. From my own study of history, the following conditions must be present in order for masculine virtues to find a healthy presence in a society: (1) institutional support from some sector of society, such as the military, an organized religion, or mercantile guilds; (2) the existence of fraternal societies, such as guilds or military orders from which women are excluded; and (3) mentors willing to instruct young men.

Unfortunately, none of the conditions needed for the cultivation of masculine virtue are present in modern America. Institutions that once nurtured it have been marginalized or destroyed, and mentorship is now a purely hit-or-miss affair.

But the seeds of our resurrection have been planted, and are slowly germinating. We do have control over ourselves, and we can integrate elements of Vergerio’s program into the training of our younger brothers or sons. By training ourselves for leadership and the hardships of life, we serve as beacons of hope for younger men who have been left with no role models, no mentors, and little hope. For ourselves, and for them, we toil.

We sharpen our swords, and await the approach of our day.

Read More: Why Being A Loner Makes You A Great Leader

Leave a Reply