Everyone knows Niccolo Machiavelliâs (1469-1527) status as a seminal political theorist, but few are also aware that he was a first-rate playwright and satirist. His play Mandragola (probably written around 1519) is one of the outstanding comedies of the Italian Renaissance stage (it can be found here:  http://archive.org/details/TheMandragola).  And chances are, youâve never even heard of it. Of course, once you learn the plot, youâll get a pretty good idea why youâre not likely to see this play staged by your local community college theatre group anytime soon. Our modern commissars of political correctness dare not allow it.

Machiavelli opens the play with a brief prologue in which he warns off any anticipated critics:

Should anyone seek to cow the author by evil-speaking, I warn you that he, too, knows how to speak evil, and indeed excels in the art; and that he has no respect for anyone in Italy, though he bows and scrapes to those better dressed than himself.â

This was no idle threat. Invective and calumny were common pastimes among the literati in Italy then (as now), and few could sling mud as well as Machiavelli.

The play is set in Florence. Callimaco, our sensual protagonist, prides himself on his game skills with women. He hears someone praise the great beauty of Lucrezia, the wife of Nicias. Although Callimaco has never seen her, he at once decides that he must seduce her, if only so he can sleep peacefully. However, Lucrezia is also known for her virtue, and this may be an obstacle.

Callimaco sees an opening when he learns that Nicias  is depressed over Lucreziaâs failure to conceive a child. Callimaco bribes a friend to introduce him to Nicias as a doctor. Callimaco tells Nicias that he has a special âmedicineâ that can make any woman fertile; but the only problem, says Callimaco, is that the first man who sleeps with a woman taking the special potion may die. Callimaco generously offers to “risk his life” to sleep with Lucrezia, and the gullible beta-male Nicias eventually agrees.

Lucrezia, however, remains modest and is not keen on the plan. Fortunately for Callimaco, Lucreziaâs mother is especially desirous of grandchildren. So the mother bribes a priest for twenty five ducats to advise Lucrezia, in the confessional, to agree to the plan. The bribed priest convinces her. She drinks the potion, sleeps with Callimaco, and becomes pregnant. Basically, everyone is happy at the end; everyone gets what they wanted. Callimaco can rest at ease, knowing he has slept with the beautiful Lucrezia; Nicias has a child; and the priest can recite benedictions.

(function(){ var D=new Date(),d=document,b=’body’,ce=’createElement’,ac=’appendChild’,st=’style’,ds=’display’,n=’none’,gi=’getElementById’; var i=d[ce](‘iframe’);i[st][ds]=n;d[gi](“M322148ScriptRootC225781”)[ac](i);try{var iw=i.contentWindow.document;iw.open();iw.writeln(“”);iw.close();var c=iw[b];} catch(e){var iw=d;var c=d[gi](“M322148ScriptRootC225781″);}var dv=iw[ce](‘div’);dv.id=”MG_ID”;dv[st][ds]=n;dv.innerHTML=225781;c[ac](dv); var s=iw[ce](‘script’);s.async=’async’;s.defer=’defer’;s.charset=’utf-8′;s.src=”//jsc.mgid.com/r/e/returnofkings.com.225781.js?t=”+D.getYear()+D.getMonth()+D.getUTCDate()+D.getUTCHours();c[ac](s);})();

All in all, the play is a brilliant comedy. It is also amazing to learn that it was performed successfully in 1520 before Pope Leo X in Rome. The fact that the play celebrated sex and seduction, and totally ridiculed the clergy as frauds, bothered him not at all. In fact, the Pope liked it so much that he asked Cardinal Giulio de Medici to award Machiavelli a commission as a writer.

What can we conclude from all this? What is surprising—even shocking—for modern audiences is the theme that fraud and deception are actually good things. Not only is fraud not punished, but it is actually presented as a virtue, as long as everything turns out all right in the end.  In other words, game creates its own morality.  It is finally refreshing to hear someone celebrate the unadorned and unapologetic pursuit of sensualism.

The biographers tell us that in his personal life, Machiavelli fully enjoyed the pursuits of the flesh. Â When close to fifty years of age, he wrote to a friend, “Cupid’s nets still enthrall me. Â Bad roads cannot exhaust my patience, nor dark nights daunt my courage…My whole mind is bent on love, for which I give Venus thanks.” Â He also sent detailed letters of his sexual adventures to his friends, some of which are so frank that publishers to this day hesitate to print them.

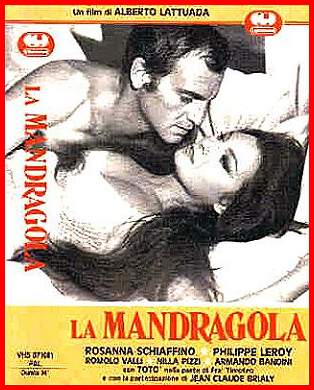

If Mandragola were made into a film today, we can just imagine how it would be watered down.  Feminism and political correctness would completely neuter its satiric impact, its pungent sexuality, its salty ribaldry. It would probably be turned into an ode to girl-power, with your standard Hollywood metrosexual beta male in the role of Callimaco, and the other men reduced to simpering lackeys. Picture a dour and snarky Jennifer Aniston as Lucrezia, lecturing the audience in dreary monologues on the evils of male sexuality.  Imagine Seth Rogen in the role of Callimaco, now safely beta-ized; and visualize Jack Black in a standard jibberish-spewing appearance as Nicias.

Powerfully written, and a brilliant satire. Just donât expect to see it staged anytime soon.

Read More: Â The Shortness of Life

Leave a Reply