I’ll shoot it to you straight and look you in the eye.

So gimme just a minute and I’ll tell you why:

I’m a rough boy. I’m a rough boy.

Rough Boy, ZZ Top

There is an old African tale about a hunter who takes his son out with him hunting one day. Early on, the man finds a small rat, kills it and tells his son to keep the rat. The day goes by, with both the father and son unsuccessful in finding any more prey. The father turns to the son and asks him for the rat he killed earlier the day. The son shrugs, and tells his father that he threw the carcass away in a bush because he didn’t think they would need a rat. The story ends with the father raising up his ax, smashing his son with it and leaving his son unconscious.

In his many seminars in the 1970’s and 1980’s, Roberty Bly would relate these kinds of short tales to men, eliciting their opinions in an effort to understand the malaise of the modern man. In response to this particular story, men would instantaneously respond to the story, recalling exactly where their own father struck them or hit them—or when they wanted their father to strike or hit them as a youth. The point wasn’t about physical violence, but about how our fathers will eventually wound us—for better or for ill—as we grow from wayward, immature boys and into confident, self-assured men.

Bly’s interest in the ritual passage from boyhood to adulthood grew over the years as he participated in these workshops. A child himself of the radical politics of the ’60’s, he was in tune with the feminist and left-wing politics of the time. In spite of that, he noticed that the men of the modern, “liberated” era were listless, low-energy shells of their father’s generation, filled to the brim with anxiety and crippling emotional conflict.

Despite the strident pronouncements of social progress by the Left, Bly couldn’t help but notice that the American psyche had been in tailspin since at least the 1950s, and the modern man was a key example of this.

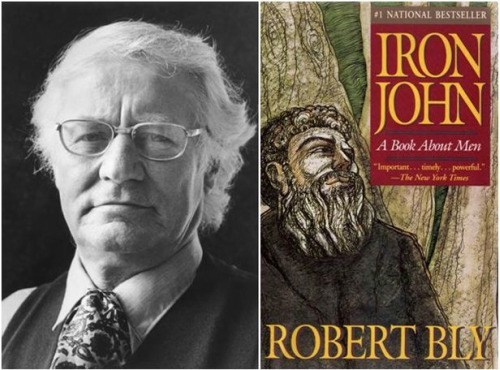

Over the course of these decades—which lead to the publication of Iron John in 1990—Bly immersed himself fully in this fledgling men’s movement. He encountered men from all walks of life—accountants, coal miners, doctors—and he noticed that they all seemed to have a universal ennui that stemmed from their childhood.

These men never really knew their fathers all that well—who he was, what he did everyday outside the home and why he seemed to just “rustle the papers in the kitchen” after supper. This mythical father was either entirely absent or was a distant figure of a sort, either dominated by “mother” or was a domineering figure in his own right.

They knew their mothers well—too well, perhaps—-and while they were in touch with the maternal side of parenting, they were impoverished by this paternal deficit. Unable to shake this general malaise, they found themselves wasting away at jobs they hated, dissatisfied with their marital relationships and had difficulty truly connecting with their children. Contrary to the grand narratives spun by feminists about patriarchy and male domination, these men were simply trying to love and be loved in return and have found themselves lost.

Iron John is the exploration of this lack of male initiation in America and its profoundly negative affects on boys as they mature into men. The books draws heavily on Jungian psychology, tales and anecdotes from varied cultures, and snips of wisdom from poets. Bly attempts—successfully, for the most part—to fuse a cultural critique of our shared values about raising boys with a discussion of a particular Grimm’s fairy tale—The Story of Iron John—in order to illuminate the steps that a boy must take in order to become a man.

The parable of Iron John is a simple one: a young prince learns to grow and become a man through the tutelage of the “wild man” Iron John. According to Bly, this “wild man”—covered from head to toe in tangled hair—represents a connection to the “deep masculine,” a sort-of wellspring of eternal masculine truth. Iron John helps guide the young prince into adulthood, learning to fight, learning to love a woman and learning to deal with humility and pride.

Throughout the book, Bly builds on the parable, providing illuminating tales from other cultures on how they shepherd their boys into adulthood. Through the use of poetry and anecdote, he breaks the parable apart into eight easily digestible parts and explains how modern men can get caught in various stages of personal growth. The disappearance of male initiation rituals at various stages in life prevents modern men from growing up in certain ways, leaving them much poorer in spirit and mind.

The book is at its best when he focuses in on the various stages of growth a boy must go through in order to become a man. Consider a couple quotes.

On the disservice American schools do to their pupils:

Father Ong notes that combative debates survive in some European universities but have almost ceased in American universities. Men who have no family tradition of lively argument may feel themselves overwhelmed in such debates. Moreover, some men and women found that they did not enjoy this way of learning the competitive mood, the aggression, the fierceness of phrase, did not please them, and some pity of the loser affected the joy of the combat.

On importance of older males in the initiation process:

In ordinary life, a mentor can guide a young man through various disciplines, helping to bring him out of boyhood into manhood; and that in turn is associated not with body building, but with building an emotional body capable of containing more than one sort of esctasy.

We know, moreover, that such initiation does not take place at any one moment or only once. It happens over and over. An Australian aborigine said something to this effect: “I’ve been doing this initiatory work with young men for over forty years now, and I think I’m beginning to get it myself.”

As one might already expect, the greatest failing of the book is the liberal sympathies of Bly. For all of his brilliant insight into male initiation and cultural practices of other countries, the book is cluttered with clumsy shots at Republicans and right-wingers. While that is distracting enough, his attempts to balance feminism with male interests makes the book tough to take seriously at times.

Feminism, by definition, is about placing power relations between men and women on a different footing without any regard as to its affect on boys or girls. Trying to balance the spiritual development of boys into men with a craven, soulless movement like feminism is a fool’s errand.

In sum, the book is excellent at what it set out to do: analyze the current malaise of modern men, understand its roots and attempt to retrieve some guidance from the past on how to move forward as men.

While the prose is certainly too flowery at times, Bly does a great job of breaking various parts of male growth down into understandable parts. The use of “The Story of Iron John” was brilliant, as is his masterful command of literary and cultural anecdotes to help shed light on the unfortunately mysterious process of becoming a man.

Leave a Reply