I still remember the time I first listened to N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton. I was in college, and a friend of mine had dubbed a tape for me and said, “Man, you need to check this out.” So I brought it back to my dorm room and let it rip. I couldn’t believe they were saying the things they were saying; no one had ever cursed like that on a record before, or spun such violent fantasies.

The attraction of the music for white kids like me with no experiences in the inner city was this: it was angry, rebellious, and somehow bizarrely life-affirming in its exuberance. In 2015, this type of music is no big deal any more. But in 1988, it was incendiary.

When I heard last month that a movie was being made about the formation of N.W.A., I decided to read Jerry Heller’s 2006 book Ruthless: A Memoir. Heller was the co-founder and producer of Ruthless Records (N.W.A.’s label), and I had been dimly aware of the various back-and-forth accusations that had been tied to the drama of N.W.A.’s breakup.

What were the roles of Dr. Dre and Ice Cube? Who had screwed over whom? Where did the blame properly lie?

Heller’s book pulls no punches. He cuts through all the posturing, all the bullshit, and all the lies that have been circulating in the entertainment world for the past twenty years regarding who did what to whom. The effect is like that of a cleansing wind.

In the mid-1980s, Heller was a worn-out Los Angeles band manager in need of a second wind. He had been a big player in the rock world of the 1960s and 1970s, managing many famous acts. But changing public tastes and a nasty divorce had left him feeling empty and in need of a new path. Heller clearly has a talent for sniffing out good music, and he sensed that rap music was on the ascent.

So he started to frequent underground rap shows in various locales in the city. He must have cut quite an unusual figure: a tall, educated, middle-aged white Jewish guy trying to get established in a black cultural niche definitely attracted attention.

But Heller was at his core an anti-establishment type of guy, he had had a lot of experience in the music game, and he never tried to be something he wasn’t. And that “realness” was what gave him credibility in the rap world.

One day, he was approached by a persistent, sunglasses-wearing kid named Eric Wright. Wright, who went by the nickname Easy-E, had been trying to meet him for weeks, finally paying a friend $750 to arrange an introduction with Heller. As Heller relates it:

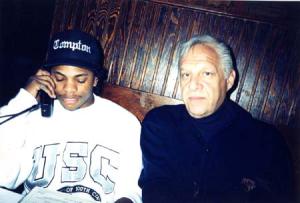

I was trying to imagine how this runt-of-the-litter twenty-three-year-old tenth-grade dropout saw me. Tall European-American, already gone a shade gray, educated, open-eyed, twice Easy’s age and outweighing him by a good eight or ten stone…”You were the first white guy I ever really talked to who wasn’t trying to collect rent or arrest me.”

Easy-E played a demo tape for Heller which contained the song “Boyz N the Hood,” and he was blown away. Out of this first meeting, the idea of N.W.A. and Ruthless Records was born. Heller knew musical genius when he saw it, and acting on blind faith, he took the biggest plunge of his life.

He contributed huge sums of his own money to start Ruthless Records, and Easy provided the talent in the form of the other members of the group (Dr. Dre, MC Ren, Yella, and eventually Ice Cube, who was only 17 at the time).

But the unlikely pairing of Heller and Easy-E worked because each provided something that the other didn’t have. Heller actually worked for Easy-E, but was paid on a percentage basis of the label’s gross revenues. Heller knew what he was worth and wasn’t afraid to say so.

After a few successful albums, N.W.A. dropped a nuclear bomb with Straight Outta Compton. And as the money began to pour in, so did the inevitable personality conflicts, business disputes, and simmering grievances. As Heller sees it, the problems began with Ice Cube’s constant complaining and unwillingness to be a team player.

Apparently he believed he should have been paid more than the other group members, and had a legion of attendants who were willing to feed his ego. He says:

Even in those early days, Cube was always difficult. At first I thought he had a chip on his shoulder just because he was younger than everybody else in the crew. Of all the attitudes, adolescent attitude—harnessed, as it is, to hormones—is the most unsophisticated. I had to laugh at Cube’s angry gangsta posturing. He still lived with his mother. But shitty human beings sometimes make great art.

But Cube’s imagined grievances (completely baseless, in Heller’s view) would cause him to leave the group and start a solo career. This would prompt a string of back-and-forth insults between him and his former bandmates. Things would eventually get even worse once a shadowy figure named Suge Knight appeared on the scene.

As Heller relates it, Knight basically held Easy-E hostage and forced him to sign away his top producer, Dr. Dre. This part of the story is painful to read, as Dre and Easy had been close friends. Heller makes it abundantly clear that Dre set up and totally betrayed his friend Easy.

Heller is aware that Cube and Dre have accused him of financial wrongdoing. To Heller, that is complete bullshit:

It’s a time-honored maneuver for African-American musicians to cry “racism” whenever they wish to leave a music contract. Not that such claims are always baseless—just that they are pretty much automatic.

In describing Ice Cube, Heller’s prose seethes with real anger. Even after all these years, the wounds caused by Cube’s words in his song “No Vaseline” and in interviews still cut deep. One can almost feel the satisfaction Heller has in relating this little story:

Ice Cube, the apostate ex-member of N.W.A., was quoted in a newspaper interview running his mouth off with an indirect dis at Above the Law [another rap group signed to Ruthless Records]…The beef came to a head at an Above the Law show in Anaheim at Circle Star Theater. Hutch [a member of Above the Law] invited Cube to their dressing room backstage, where he gave him a savage beating. “[Cube] was crying like a little girl,” crowed Easy. No love lost there. Ice Cube was terrified.

But it perhaps in putting to rest the allegations of financial wrongdoing that Heller has his finest moment in the book. In this passage, Heller rises to red-hot eloquence:

All these years I’ve never answered the allegations of financial impropriety leveled against me, first by Cube and then by Dre. Now that I’m writing this book, I feel compelled to answer those allegations on behalf of my longtime partner, Easy-E…And I say to you, Cube, that the amount of money you earned at Ruthless Records didn’t have anything to do with anyone’s hand in the cookie jar. It was pure mathematics, baby—not your strong suit, from what I hear about the producers and writers you utilized at your own record label. They were screaming about not getting paid just like you used to scream…

Here are the numbers spelled out: For every record and merchandising dollar N.W.A. brought in, Ruthless Records took twenty-five cents off the top. The label deserved it. That’s a fairly conservative percentage. Ruthless sponsored your time in the studio, your tours. The label bought you your fucking pencils. That leaves seventy-five cents to split five ways, between the five members of N.W.A., which means everyone gets fifteen cents out of every dollar.

Heller then goes on to break down the financials in a methodical and devastating way, and points out that neither Cube nor Dre have ever sued him for anything. The reader will form his own conclusions from all this. The book is not without flaws. Heller feels compelled to spend pages talking about his experiences managing rock acts in the sixties and seventies like Van Morrison and Creedence Clearwater Revival, but these musings detract from the focus of the book, and held no interest for me.

The takeaway

I like Jerry Heller’s attitude about life. His philosophy is simple: if you don’t like me, I’m not going to like you. He mentions how rapper The D.O.C. disliked him for some unstated reason. Heller gave it right back to him: if you don’t like me, go fuck yourself. Life is too short.

I’ve read that the new movie Straight Outta Compton was made without any consultation with Jerry Heller. Easy-E’s son apparently wasn’t even given the chance to read for the part. But Ice Cube’s son is playing in the film. The fact that the movie was produced by Dre and Ice Cube suggests the reasons why one version of history is being promoted over another.

“Only two guys were present at the formation of Ruthless Records,” Heller said in a recent interview, “And they were me and Easy. And one of them is now dead.” Heller went on to say that he’d be watching the opening of the film on its first day, with his lawyers. “And if I’m not portrayed accurately, then that’s going to be addressed. I owe that much to Easy.”

Even if you have no interest in rap music or the entertainment industry, Ruthless: A Memoir is worth reading for what it teaches us about the Shakespearean themes of power, riches, and friends betraying friends. These themes are timeless for a good reason.

Heller had wanted to call his book Niggaz 4 Life. At first, I thought the title sounded ridiculous. But after reading the book, I think it sounds just right (Easy would have loved that title). He survived in a rough world with rough characters, and gave as good as he got.

He’s got no regrets, and no apologies. He helped make history, and he knows it. That alone makes the book a great read. If anyone can claim the title of being a Nigga 4 Life, it’s Jerry Heller.

Ya did good, Jerry. Thanks for the 1990s memories. Much respect.

Leave a Reply