Greatness is more often the result of years of incremental, patient labor than it is the sudden phosphorescence of a single incident. Gradually but persistently, like the drips of water falling in a cave and accreting mineral formations, the labors of the great man may take many years to produce results. But when the results to come, they can move awe in the soul. We, the spectators, stand in wonder at the finished products, but forget the painstaking, backbreaking toil that produced them. Overnight success, someone once said, usually takes about ten years.

In fact, it usually takes a lot longer than that.

Andreas Vesalius came from a Brussels family with a notable history in the medical profession. By all accounts, as a boy he was consumed with a passion for the natural world, and eagerly soaked up all available information on biology, anatomy, and medicine. His special passion was dissection, for which he developed a prodigious talent. He showed signs of genius at an early age: at twenty two years old he was able to lecture to pupils in Latin, and was able to read the medical works of Galen in the original Greek.

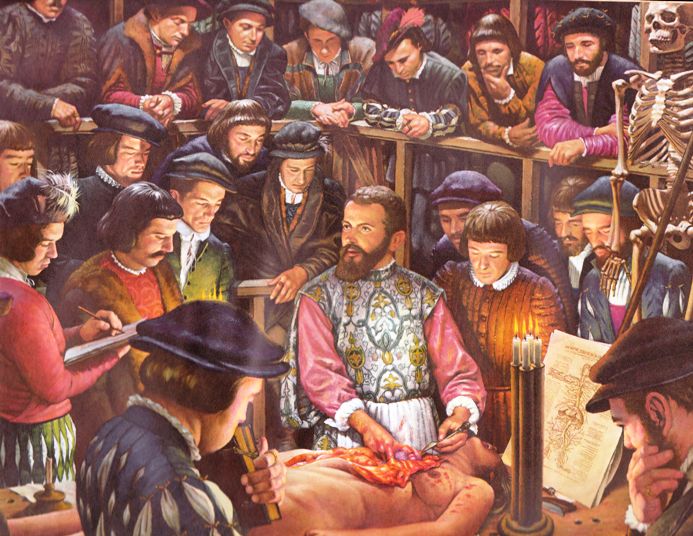

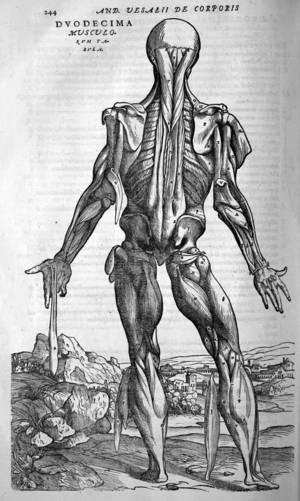

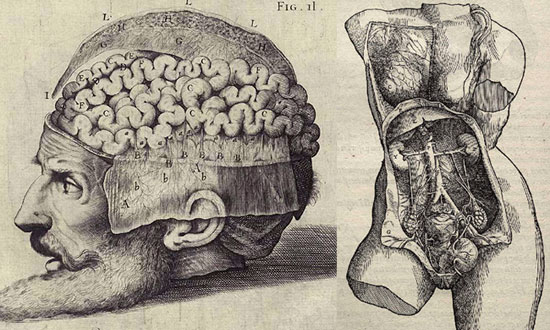

Plate detail from Vesalius’s masterwork, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (1543)

Medical science in Europe at the time was held hostage by the ancient texts of Galen, Celsus, and Aristotle, and by traditional theological disapproval of anatomical research. Galen’s work, although brilliant in its day, had not kept pace with the advancement of learning in the intervening millennium; and Vesalius found the slavish devotion to his texts at Louvain schools to be suffocating. Secretly, he and friends prowled the charnel houses for cadavers to bring into the lecture halls and dissect. He suffered no fools and, like many great men, found it hard to keep his passions under control. He soon found it prudent to leave Louvain and relocate to Padua, Italy, where he received his doctorate; in 1537, the Venetian authorities appointed him professor of surgery and anatomy at the University of Padua. He was only twenty three years old.

Vesalius kept meticulous and voluminous notes of his researches over many years, a fact that would be of inestimable value in the next phase of his life in Italy. From 1541 to 1543, while working with colleagues on a complete revision of the medical texts of Galen, he became more and more aware that an entirely fresh perspective was needed. Traditional ways of thinking would have to be thrown out completely.

Revolutionary moments in science seem to come when a pioneer—either through a flash of insight or simply out of desperation— finally jettisons the old paradigms and adopts an entirely new model. So Copernicus and Kepler finally realized that the Ptolemaic orbital systems of the sun and earth could not be reconciled with the observed astronomical data; and so Max Planck, in desperation at his inability to explain the nature of blackbody radiation, finally adopted a quantum-based mathematical model that could account for his observations. Vesalius had reached a point of no return: regardless of the cost, he resolved to drag the science of anatomy, kicking and screaming, into the modern world. The result was the greatest medical work ever written.

In 1543, at the age of twenty nine, Vesalius published in Switzerland the first edition of De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Structure of the Human Body). No one had ever seen anything like it before. Printed in 663 glorious folio pages, it contained nearly 300 original woodcuts which by themselves could have stood independently as works of art. Many of the engravings were made with Vesalius’s own hand. Here was finally revealed the intricate and detailed structure of every part of the human body, in a methodical, confident way that was staggering in its breadth and scope. Everything in the Fabrica was based on original first-hand research, with no reliance on, or allowance made, for hearsay or superstition. It was momentous in the profoundest sense possible.

It is perhaps difficult for us now, several centuries removed, to realize how revolutionary his revelations were. Knowledge of the body and its operations is relatively common now, but this was not always so. We must remember that the entire basis of modern medicine rests on a detailed factual understanding of how the body works. And Vesalius’s labors showed the way. For the first time, here was described the ventricles of the heart, the operation of the blood vessels, the uterus, the liver, the brain, the skeletal system and bone structure, and the function of the other internal organs. Vesalius had mapped the body with the same masterly thoroughness that Johannes Kepler described the orbits of the planets. And he laid the observational groundwork that later generations would build on.

Expectedly, he was resented by older colleagues and the theological authorities whom he had no use for. Like many great pioneers, he made enemies everywhere who feared the overthrow of the existing paradigms. Some academics tried to explain Galen’s errors by claiming that the human body had “changed” anatomically since antiquity. In frustration at the pettiness of his peers, Vesalius left Italy and took a position as medical advisor at the court of Charles V of Spain, where he found himself a foreigner at odds with the native Spanish physicians. It is not unlikely that he was also under suspicion by the Inquisition, which never forgave his bold refutation of religious scripture with applied science. He issued an expanded second edition of the Fabrica in 1555, which contained even more original research and observations.

His powers remained unequalled. In 1562, the king’s beloved only son suffered a concussion and serious head trauma from a fall. Vesalius urgently recommended a brain operation which involved opening the skull; the diagnosis was rejected with horror by the king’s sycophantic entourage and other doctors. As the prince neared death, and with the royal court in near paralysis, Charles finally consented to let Vesalius perform the surgery. Vesalius undertook the job fearlessly, fully aware what was at stake. It was a complete success. The prince recovered in eight days, and Vesalius’s powers gained nearly mythic status.

Like many men of genius, he had the faults of his formidable abilities. Far ahead of his contemporaries, he found it difficult to extend forbearance to foolery, and impossible to leave ignorance unanswered. It was in his nature. His flame burned brightly, yet with tragic brevity: men of action find it difficult to relax, and to know when to stop. For reasons that are not clear, he eventually left Spain to go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem. He reached the holy city, but was shipwrecked off the island of Zante in Greece on his return voyage in 1564 and died of exposure. He was only fifty years old.

Vesalius’s mapping of the human body laid the observational groundwork for later discoveries by the physicians Servetus and Sir William Harvey. As a physician and scientist, he had no equals. But he paid a high price for his genius. Working under difficult conditions and in hostile environments, he developed a protective shield of curtness and pride that often wounded his friends and colleagues. He was generous to a fault with his friends, and had none of the vindictiveness or petty jealousies that afflicted his peers. When hardly thirty years old, he was able to dethrone the Galenic view of medicine and anatomy that had held sway in Europe for over a thousand years. He was a prisoner of his time, yet scaled the heights of immortality.

The original woodblock engravings of the Fabrica , lovingly preserved by Vesalius in his lifetime, were lost after his death. They were miraculously rediscovered at the library of the University of Munich in 1893. During the Second World War, they were destroyed in a bombing raid. So the folly of man can obliterate in an instant the treasures of the ages.

In an age where the boundary between art and experimental science was often indistinct, his Fabrica remains a masterpiece of both. An outsider in many environments, he did his best to reconcile his restless ambitions with the intolerance and ignorance of the era in which he lived. He believed passionately in the progress of mankind, and he exhausted himself in his lifelong pursuit of knowledge, yet he never lost faith in the redemptive power of scientific inquiry, even in an era which believed firmly in witchcraft and demons.

Who among us has the moral courage to rise about the limiting beliefs of our era, and who will permit his spirit to soar into areas of inquiry that may bring strong disapproval? And who has done it with such masterly confidence, and such single-minded devotion? Despite his human faults, he ennobled his patient labors with the inspiring dignity of a scholar and the courageous objectivity of a true scientist. He was a seeker and a pioneer. And he was the greatest physician in history.

Read More: The Greatest Adventure

Leave a Reply