The French philosopher Joseph de Maistre once perceptively commented: “I do not know what the heart of a rascal may be; I know what is in the heart of an honest man; it is horrible.” Even the most kind-hearted of us would hesitate to expose his innermost thoughts to public scrutiny. Barbarous thoughts and inclinations are always bubbling just beneath the surface, and this is why it is so important for man’s baser instincts to be kept firmly in check by a moral code that carries with it the authority of experience, and the lineage of antiquity.

More and more, we are becoming unwelcomingly acquainted with the mentality of the fanatic. Whether modern society–with its corrosive influence on ancient moral codes and its titillating stimulus of man’s baser instincts—is breeding more and more of these people, or whether modern information technology simply unmasks them easier than in the past, is not entirely clear. In either case, an understanding of the mentality of the fanatic is important. We will discuss a few of his salient features here.

The fanatic sees the world in absolutes. For him, there are no mixed tones of grey. It is all one thing, or all the other. The world is a battleground between the forces of good and evil, and only he himself is fully aware of the dimensions of this conflict. He is blind to the nuances in things, because he can only see the world through the lens of his own monomania.

The fanatic sees himself as under constant attack. His projection of the all the world’s evils onto the demonic “other” creates this Zoroastrian conception of the universe, where all of creation is held hostage to this battle between the forces of Good and Evil. If he lets his guard down for an instant, the evil Other will overwhelm him.

This is why the fanatic often takes on the appearance of the hunted animal: furtive, opportunistic, and ready to sacrifice himself. It is this aspect of his thinking that makes him so dangerous. A good measure of self-hatred is also thrown into the mold of personality. The fixation on the evil Other makes the fanatic obsessed with purging traces of the evil Other that may be hidden in himself.

The fanatic’s certainty can make him seem persuasive. Most people, lacking firm convictions of their own about almost everything, are attracted to the prospect of someone who announces his dogmas with absolute certitude. It is this certitude that aggrandizes his standing.

People with weak wills, and those unable or unwilling to think for themselves, can surrender the responsibility of thought to someone else. The messianic zeal with which the fanatic announces his plans makes him, in his early stages, an attractive and fascinating figure with women, simpletons, and persons of bad character; and it is only when it is too late do these hangers-on realize the folly of their trust.

The fanatic lacks empathy for the sufferings of others. Because he is consumed by the burning responsibility of his mission, he is blind and deaf to the cries of those whom he persecutes or violates. For him, they do not matter. It is this ability to disconnect his moral programming that gives the fanatic the power to commit frightening atrocities. The fanatic is frequently the product of some abusive environment himself, and becomes conditioned to the necessity of violence and brutality as a means of implementing his plans.

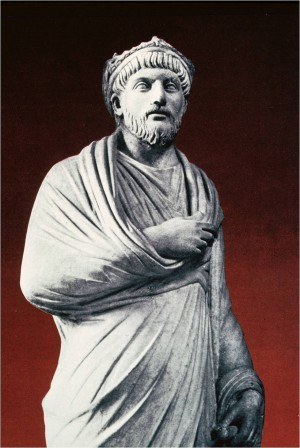

Some historical examples bring these points into focus. The Roman emperor Julian (A.D. 331-363) experienced the murder of his father and immediate family by his cousin Constantius. He was brought up in isolation, under the watchful eye of the emperor’s spies.

These experiences made him identify the religion of his oppressor Constantius (i.e., Christianity) with evil. When Julian finally came to wear the imperial purple himself, he became a fanatical persecutor of the Christian religion. It was, for him, synonymous with illogic and malignancy.

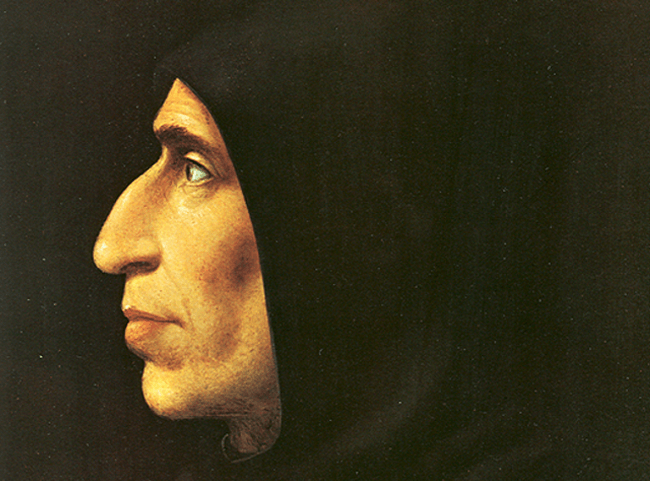

Another example is provided by the fanatical career of the Dominican friar Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498). Florentines were initially attracted by is powerful sermons about the prevalence of vice and the imminent Kingdom of Heaven; his eloquence convinced many of his prophetic powers. He condemned art and scholarship as the products of vice, and sought to destroy these things, as well as regulate the sexual behavior of the fun-loving Florentines.

For a time, he was humored. But moralistic preachers tire everyone after a while, especially when they begin to attack the rich and powerful. Pope Alexander VI excommunicated him, and eventually had him executed.

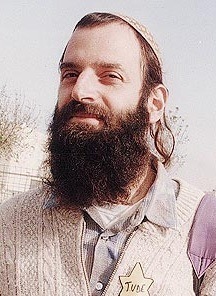

In our time, religious and ideological fanaticism has seen something of a resurgence. Examples are depressingly plentiful. Extremists are found in every religion and every ethnic category. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed leader of ISIS, is addicted to the slaughter of his sectarian enemies, believing himself to be ordained by God for this task. Of a similar mentality was the Zionist fanatic Baruch Goldstein, who believed it his holy mission to enter a place of worship (the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron) in 1994 and gun down twenty-nine innocent people.

To such people, human lives are not important: what matters are their monomanias. By kindling bonfires and butcheries, they seek to burn out the malevolence that flames within their own hearts. This was what Savonrola sought in his so-called “Bonfires of the Vanities” in Florence. When this proves impossible, they destroy themselves, as Baruch Goldstein was consumed by a lust for murder. It is this self-destructive impulse that makes the fanatic so recklessly “brave.”

We must cultivate our powers of rational thought, and sympathy for others, so that we may keep our more intolerant instincts under control. The fanatical “reformer” often turns out to be just as intolerant as the tyranny he proposes to replace. “Whenever the spirit of fanaticism,” wrote historian Edward Gibbon, “at once so credulous and crafty, has insinuated itself into a noble mind, it insensibly corrodes the vital principles of virtue and veracity.”

The first lesson of philosophy, it has been said, is that perspective matters. We must try to see the world through the perspective of others, if we wish to understand their behavior. Certainty, under whatever guise it takes, is murderous.

Read More: You Have To Learn To Love Rejection

Leave a Reply