The daring exploits of John Paul Jones during the American Revolutionary War earned him international fame as America’s first great naval hero. A Scotsman by birth, he possessed all the sternness, willpower, and volcanic temperament of his people, qualities which made him a formidable commander on the high seas; but like most great men, his virtues contained the seeds of his faults. After the war ended in 1783, Jones found it difficult to accommodate himself to the politics and maneuverings of the peacetime military. His fighting skills and experiences suddenly counted for little, as the new country proceeded to demobilize and concentrate on commerce.

A fighting admiral, he could not suffer fools or endure the subtleties of diplomacy, and he was at pains to appease the bureaucrats in Congress to secure a position for himself as head of the fledgling U.S. navy. When funding and ships failed to materialize as promised, Jones felt shunted aside and unappreciated. Bitterly disappointed with his prospects in America, he sailed for Europe, never to return.

He found eventual employment, incredibly, with the Russian Empire, and became a favorite of Catherine the Great, slavicizing his name to Pavel de Zhoves. But even there, his career prospects eventually dried up, and he found himself in Paris in 1790. He died two years later, exhausted and embittered, and still chasing his ambitions. His death went unnoticed in the United States, and his funeral was attended by a scant few close friends. A knight permanently in search of a liege lord to serve, he had found little rest while he was alive, and he had been unable to recast his identity in a way suitable for a peacetime life.

In the end, he realized that this world, and everything in it, is but a maya of transitory phantoms, melting into the swirling mists of our own perceptions.

A century passed. At the dawn of the twentieth century, the United States had been transformed from a provincial backwater to an industrial powerhouse. Interest had been reawakened in the heroes of the Revolutionary War. Historians gradually began to realize that John Paul Jones had had a remarkable career, and was the country’s first great fighting admiral. But no one seemed to know what had happened to him. Jones had died at the height of the French Revolution; and in the upheaval and turbulence of the period, records had been lost, mutilated, or scattered. Where he had lived, and the location of his final resting place, were completely unknown.

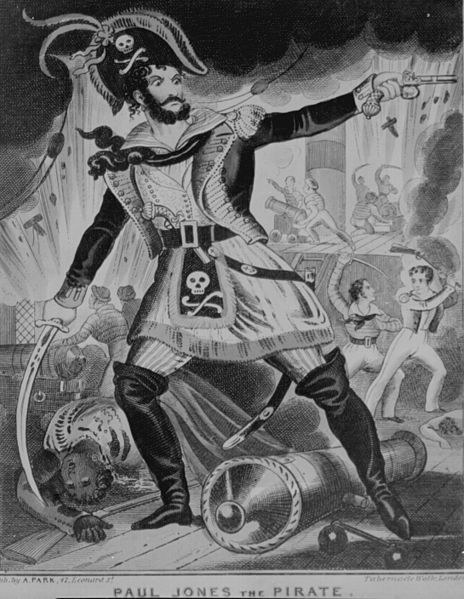

A wartime British caricature of Jones, who was seen as a “pirate”

The U.S. ambassador to France, Horace Porter, was a quiet and industrious man with a keen interest in naval history. He was personally outraged that an American national hero had been so cruelly served by his adopted nation, and he resolved to put the matter right. In 1899 he embarked on a personal quest to locate Jones and return him to America for a proper burial. He was acting purely on his own, as a private citizen.

But where to start? He found that the death certificate had been consumed by a building fire in 1871. Luckily someone had made a copy of it in 1859, and this copy had been hidden away in a mountain of records in an old archives building. According to the document, Jones’s death occurred on July 18, 1792. Other documents yielded other clues. A letter from one of Jones’s friends who had attended the funeral mentioned that the coffin had been encased in thick lead “in case the United States, which he had essentially served and with so much honor, should claim his remains, they might be more easily moved.”

Porter was shocked to discover that the American government had not even paid for Jones’s funeral. This burden had fallen to a friend of the admiral’s named M. Simoneau, who had paid roughly 500 francs for Jones’s leaden coffin, the embalming of the body in alcohol, and the outer wooden coffin. Moved to chagrin and shame by the revelation, he tried to find a descendant of Simoneau’s to reimburse, but to no avail.

At this point Porter had to resort to guesswork, his remaining leads having run cold. Foreign non-Catholics in Paris such as Jones would most likely have been buried in the St. Louis Cemetery. A search of the graveyard records found that they were fragmentary and incomplete, a likely consequence of the all-consuming fury of the French Revolution. The missing records miraculously turned up in a Paris library, and Porter was back on the trail of his prey: the records proved that Jones had indeed been buried at the St. Louis Cemetery.

But further problems remained. The cemetery had been sold in 1796 by France’s revolutionary government to a dodgy private building contractor named M. Phalipeaux, who then (probably illegally) swept away the headstones and erected commercial buildings on the site. Porter was further disturbed to find that the site later had become a dumping ground for the cadavers of horses and dogs.

Porter approached the owners of the property (today located at the corner of Rue Grange-aux-Belles and Rue des Ecluses St. Martin) to request permission to conduct some excavations on the land. But they demanded so much money from him that he thought the best course of action would be to walk away and let the matter sit for some time. He then quietly re-approached the owners after 24 months, and explained he was a private citizen financing the project out of his own pocket. An agreement was eventually reached, and shafts were sunk on the land in search of the admiral’s casket.

The streets of Paris, which conceal ancient secrets

Eventually, after probing the entire property and sifting through garbage and animal skeletons, five caskets of lead were recovered. All of them save one were marked with identification plates. The unmarked one, Porter concluded, had to be Jones’s casket; during the chaos of the French Revolution, no proper engraver could be found. The casket was opened, and a well-preserved corpse was found wrapped in linen and straw, which matched old portraits and a marble bust of Jones. A detailed examination of the body done at the Paris School of Medicine established beyond doubt that the body was that of John Paul Jones.

President Theodore Roosevelt, hearing of the recovery of the remains of Jones in Paris, was deeply moved by the pathos of the story. With his usual flair for the dramatic, Roosevelt decided to send a squadron of warships to carry the body back to Annapolis, Maryland for proper burial.

Porter himself faded from history. His tenacity and devotion had made the recovery of the body possible, but he was never reimbursed by the U.S. government for his efforts. His personal expenses had run into the tens of thousands of dollars, which were hefty sums in those days.

Time heals old wounds, and inflicts new ones.

Memorial services were held on April 24, 1906. President Roosevelt spoke the following words:

“Remember that no courage can ever atone for the lack of preparedness which makes the courage valuable. And yet if the courage is there, its presence will sometimes make up for other shortcomings; while if with it are combined other military qualities, the fortunate owner becomes literally invincible.”

Roosevelt chose April 24 as the day for commemorative services. On that very day, 138 years before, Jones had captured the British man-of-war Drake.

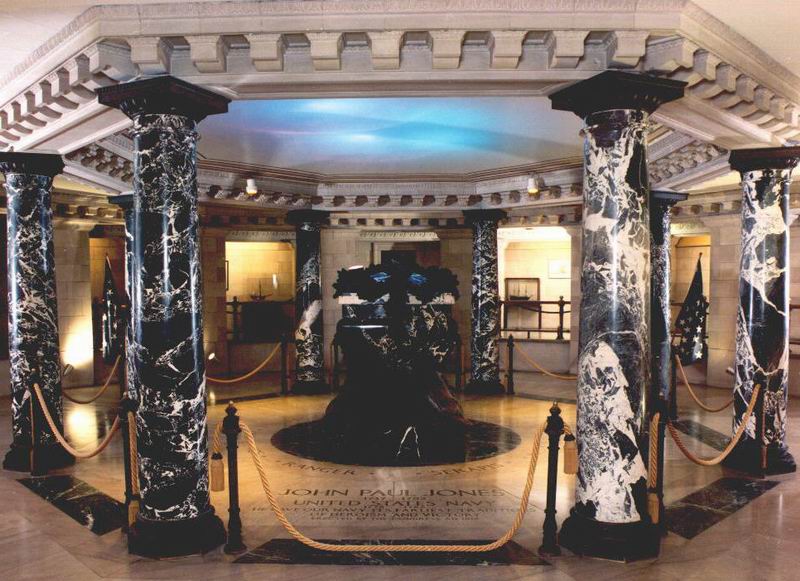

In triumph and pity, the remains of America’s first great maritime warrior were entombed in their final resting place, while mourners prayed for the repose of his soul. After 130 years, the man who had only just begun to fight finally lowered his spyglass, sheathed his cutlass, and entered the Pantheon of Heroes with a measure of silent dignity and crowning gratitude. It was his homecoming. It was without doubt his greatest victory.

Read More: A Sea Battle For The Ages

Leave a Reply